From Religious Conflict to Institutional Sovereignty: Festus Keyamo on Murdered in the Name of God

In the early 2010s, as the smoke of religious and civil unrest rose across Northern Nigeria, many observers watched from a distance with a mix of despair and detachment. However, for Obehi Ewanfoh, a storyteller and researcher deeply invested in the African Diaspora experience, distance was not an option. Ewanfoh embarked on a rigorous research journey titled “Murdered in the Name of God,” a project designed to peel back the layers of religious violence and uncover the systemic rot beneath the surface.

Learn How to Leverage Your Story through our Story To Asset Framework.

This journey took him from the historical corridors of Italy, where he interviewed religious leaders to compare European historical conflicts with contemporary Nigerian struggles to the heart of Nigeria in 2013.

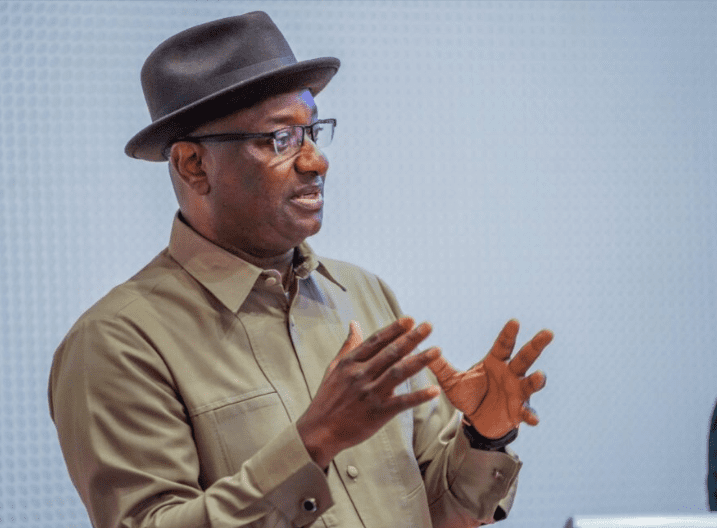

It was there that he sat down with Festus Keyamo, then a human rights lawyer and advocate for the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), and currently Nigeria’s Minister of Aviation and Aerospace Development.

Through the lens of Ewanfoh’s “Story to Asset” framework, this interview remains a pivotal piece of intellectual property.

Before we examine the insights Festus Keyamo shared during Obehi Ewanfoh’s 2013 visit to his office in Warri, Delta State, we must first understand the structural rot that makes such a transition necessary.

Drawing from the research of Dr. Olabode Agunbiade in 2024, we can measure the true weight of this challenge through the lens of national security and economic development.

The Economic Impact of Insecurity in Nigeria

The pervasive insecurity in Nigeria has fundamentally dismantled the country’s productive capacity, shifting the national socio-economic landscape from growth toward a state of survival.

As the 3rd most terrorized nation globally, Nigeria faces a severe depletion of its human capital, with over 3.3 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) unable to contribute to the workforce. In the Northeast specifically, this social dislocation has resulted in abject poverty for 71.5% of the population and formal unemployment for 60% of residents.

The agricultural sector, which accounts for 22.35% of the total Gross Domestic Product and employs over 70% of the population, has been particularly devastated; banditry and ethno-religious violence have forced farmers to abandon their lands, triggering high inflation and acute food insecurity that threatens the very foundation of the national economy.

See also Applied Indigenous Knowledge Systems: Exploring the Application in African Psychology

Beyond the immediate loss of life and infrastructure, insecurity acts as a massive “tax” on economic development by stifling investment and draining government resources. The climate of fear has eroded investor confidence, leading to a steady decline in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) as multinational corporations close operations and flee unstable regions.

For local businesses, the cost of operations has skyrocketed due to the necessity of private security spending and the loss of man-hours caused by curfews and shortened bank operating times.

This systemic instability is further exacerbated by the proliferation of small arms and light weapons (SALWs) and the lucrative “ransom economy,” which creates a cycle of criminal opportunism.

Consequently, government revenue is diverted away from critical socio-economic infrastructure, such as the 10.5 million out-of-school children, and toward reactive, burdensome security expenditures that have yet to stem from the rising tide of unrest.

The Disconnect: When Government Becomes an “Alien Authority”

One of the most striking revelations from Ewanfoh’s dialogue with Keyamo was the profound psychological and physical distance between the Nigerian state and its people. Keyamo described the government not as a protector, but as an “alien authority.”

In a functioning society, the social contract dictates that citizens provide loyalty and taxes in exchange for security and infrastructure. In the Nigerian context of 2013, Keyamo argued that this contract was non-existent.

- Self-Help as a Survival Strategy: In the absence of state-provided water, electricity, and security, Nigerians turned to “self-help.”

- The Health Crisis: Keyamo noted that those suffering from illness were often left to “wither and die” without any government intervention or social safety net.

- The Legitimacy Gap: Because elections were viewed as falsified, those in power felt a “reciprocal loyalty” not to the voters, but to the political “godfathers” who placed them there.

For Ewanfoh, this research underscored a core pillar of his later work: Sovereignty. When a system fails to serve you, you are merely a tenant in your own country. True sovereignty begins when the community builds its own institutions, a philosophy that eventually birthed AClasses Academy.

The Diaspora Dilemma: From Brain Drain to “Foot Soldiers”

A significant portion of Ewanfoh’s research focuses on the African Diaspora. During the 2013 interview, Keyamo issued a blunt, almost provocative challenge to Nigerians living abroad.

He argued that many in the Diaspora had “no business” being away, lamenting the massive amount of energy being pumped into the economies of Ireland, the UK, and the US instead of home.

“You can’t stay abroad and begin to look through the window and criticize… Come and do it yourself, come and join us now; come and see how it is here,” Festus Keyamo, 2013.

Keyamo’s critique touched on a sensitive nerve: the difference between digital activism and physical presence. He highlighted that while social media mobilization is a tool, it only becomes a “Sovereign” force when combined with “actual street protest” and personal involvement in the economy and politics.

Ewanfoh’s subsequent work with the Obehi Podcast, which now boasts over 1,000 episodes, seeks to bridge this gap.

Rather than just calling for a “return,” Ewanfoh helps Diaspora leaders transform their unique experiences into “assets” that can influence their home countries through investment, intellectual exchange, and institutional building.

The Politics of Violence: Religion vs. Self-Determination

In his quest to understand the “Murdered in the Name of God” phenomenon, Ewanfoh pushed for a comparison between different types of conflict.

And Keyamo provided a sharp distinction between the MEND movement in the Niger Delta and the Boko Haram insurgency.

Comparative Conflict Analysis

| Feature | Niger Delta (MEND) | Boko Haram |

| Objective | Self-determination & Resource Control | Imposition of Ideology (Islamist State) |

| Territoriality | Limited to their own territory | Expansionist (Lagos, Delta, etc.) |

| Response to Dialogue | Willing to drop arms for negotiation | Initially rejected amnesty (“We don’t need it”) |

| Root Cause | Economic Marginalization | Political Manipulation & Lack of Opportunity |

Keyamo argued that religion is often a “facade.” The real recruiting factor is the lack of meaning in people’s lives. When young people have no jobs and no stake in the economy, they become “recruitable” for any cause that offers them a sense of power or purpose.

This is a classic example of what Ewanfoh calls Economic Tenancy—where individuals, having no assets or institutional backing, are easily exploited by destructive narratives.

The Cost of Institutional Failure

To understand the gravity of the situation Ewanfoh was researching, one must look at the data from that era (circa 2012-2014):

- Human Toll: According to the Council on Foreign Relations’ Nigeria Security Tracker, deaths from political and religious violence surged during this period, with thousands of lives lost to Boko Haram and communal clashes.

- Economic Impact: The World Bank estimated that the North-East of Nigeria lost billions of dollars in infrastructure and agricultural output due to the insurgency.

- The Diaspora Contribution: Despite the “brain drain,” the Central Bank of Nigeria noted that Diaspora remittances remained a vital lifeline for millions of families, often bypassing the “alien authority” of the state to provide direct social services (healthcare, education).

Business Lessons from the “Story to Asset” Framework

Ewanfoh’s research into conflict and governance isn’t just for historians; it provides vital lessons for modern business owners and professionals:

- Own Your Narrative: Keyamo’s ability to frame the Niger Delta struggle as a legal right to “self-determination” allowed him to gain international visibility. In business, if you don’t define your “Story Asset,” the market (or your competitors) will define it for you.

- Build Institutional Sovereignty: Just as Nigerians provided their own water and power, your business must build internal systems that don’t rely on volatile external factors. Create a “Sovereign” brand that your audience trusts more than the general market noise.

- The Power of Mobilization: The 2012 “Occupy Nigeria” protests (referenced in the interview) showed that when people are united by a single, clear “story,” they can force even an “octopus government” to retract. As a business leader, how are you uniting your “foot soldiers” (your team and customers) around your vision?

Conclusion: Turning History into Legacy

The 2013 interview between Obehi Ewanfoh and Festus Keyamo serves as a time capsule of a nation in crisis, but also as a blueprint for the “Story to Asset” methodology.

See also Taking a Stand Against Violence: The Triumph of Ruth Tebitendwa Kirabo

It shows that whether you are a lawyer fighting for a region, a researcher documenting the cost of violence, or a Diaspora professional looking to make an impact, your power lies in your Sovereignty.

Obehi Ewanfoh has moved from documenting the “murdered” to empowering the “living” through the Obehi Podcast and AClasses Academy. He continues to prove that when we own our stories, we move from being tenants of our circumstances to being the architects of our legacy.

Is your professional story working for you, or are you just a tenant in your industry? Book Your Free 15-Min Legacy Call Now and let’s turn your journey into your greatest asset.