Back To The Superiority Of The African Ethical Paradigm

In this article, Dr. Luyaluka talks about the return of the Superiority of The African Ethical Paradigm. Enjoy the reading and let us know your thoughts in the comment section below.

Download the first chapter of The Storytelling Series: Beginners’ Guide for Small Businesses & Content Creators by Obehi Ewanfoh.

Introduction to The Superiority Of The African Ethical Paradigm

Why do we have to care about ethics? We live in a time where postmodernism has enthroned the destruction of any notion of absolute value. The narrative of one’s group has been set by this Western philosophy as the determining element even in the domain of ethics.

This implies that, if we Africans don’t have a solid basis to anchor the validity of our ethical norms, we will be drawn towards lower moral values that are imposed willy-nilly by the West.

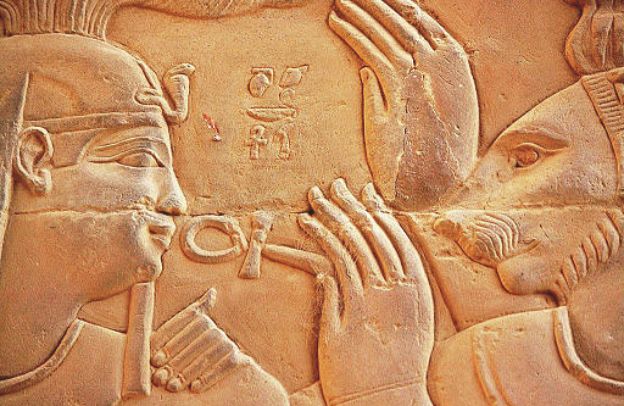

Moreover, the migration of African ethnics from the north to the south of Sahara has brought not only a theological devolution but also an ethical devolution that needs to be understood. History teaches us that any knowledge in ancient Egypt was underpinned by religion.

Now, this religion can be proven an exact science. Thus solar ethics, i.e., ethics as defined by solar religion and epistemology, had a strong religious and normative stance that needs to be reintroduced in the different trends of our cultures in order for Africans to resist scientifically to any moral debasing influence.

The Kemetic Cosmological Argument

We said above that African traditional religion (ATR), in its original trend, is an exact science. This nature of our religion can be proven thanks to the kemetic cosmological argument (KCA) to be the very brand of the religion of ancient Egypt and Sumer. That original nature of ATR has been kept intact in Bukôngo, the Kôngo religion. The KCA can be summarized as follow:

- As an aggregate of individualities, our temporal universe is individual.

- An individual temporal universe is naturally the product of an individual creator.

- The individual nature of this creator calls for the existence of other similar creators being at least potentially causative.

- Under the hypothesis that any creation abides in its creator, there is an ultimate cause including all the above-deduced potential and effective creators. This ultimate cause is the greatest possible being, the Supreme Being.

- The Supreme Being is immutable and indivisible, otherwise, there must be a principle of his mutability and divisibility greater than him, this is impossible.

- God, the Father-Mother, being indivisible, each effective and potential creator, each Child of God, as a manifestation of an individuality included in the Most-High, expresses his fullness (the Logos) in an individual manner.

This summary introduction of the KCA depicts theism which includes: a Supreme Being, a creator of this temporal universe, and the Logos. This is congruent with the theism of ancient Egypt (Sole Lord, Atom, and Ptah), Sumer (Anu, Enki, and Enlil), and Bukôngo (Nzâmbi Ampûngu Tulêndo, Mbûmba Lowa, and Mpina Nza). (For the full version of the KCA see our books titled Bukôngo & the Theocentric Big-bang Cosmology).

The KCA can be extended to all the essential doctrines of a salvational religion. Since every doctrine of the KCA evolves deductively from the previous one, they cannot contradict each other.

Thus, being a set of deductive and coherent truths, the KCA is an exact science. Hence, the congruence of the KCA with solar religion, the religion of ancient Egypt and Sumer, leads us to the conclusion that, in its original trend, the ATR is an exact science.

It follows that, contrary to the speculative ethics enforced by the philosophy of postmodernism, any ethics drawn from this African religion-exact-science can only be normative and based on strong values. So were the ethics of ancient Egypt based on the doctrine of the maât.

The Scientific Nature of the Ethics of the Maât

African ethics has always been religion-based, scientific, and normative; as can be seen in the notion of the maât. The main meaning of the maât is “to be true”. In a paper titled Maât notre ideal (Maât our ideal), this Egyptian concept is defined as “justice, order, and righteousness.

It is the infallible judge dispensing his qualities for the good functioning of the universe”. This clearly shows that the concept of order, truth, and love are central to the maât.

The KCA shows that God, the Most High, has endowed a precise individuality to each of his Children, thus avoiding infinite confusion. Hence, God is not only an infinite intelligence but also the principle of order.

Moreover, God expresses in each of his Children his own fullness, this act is an expression of affection. Thus, in expressing an infinite affection to an infinite number of Children, God must be Love, the principle of love.

It must be added also that due to his absolute immutability, God cannot deprive the Child of God of the Logos. Thus, the Father-Mother is eternally loyal to the Child. Expressing a quality of truth, i.e., loyalty, to an infinity number of Children, God must be Truth, the principle of truth

We infer from this deduction of the KCA that, as the manifestation of order, love, and truth, the principle of maât finds its explanation in solar religion. Thus, being the outcome of exact science, i.e., solar religion, solar ethics was in ancient Egypt religious and normative.

It was not the result of speculation like in Western philosophy. The maât is the manifestation of the celestial order on earth.

The KCA and the Ethics of Ubuntu

Since the scientific nature of solar religion has been kept intact in Bukôngo, we can conjecture that the original religious and normative nature of solar ethics has been also kept in it. The great ethical line of the Bantu ethics has been proven to be ubuntu.

The principle of ubuntu can be proven to stem from the double nature of the Logos. The KCA proves that the Logos is the manifestation of the fullness of God in his Children.

Now, the Children of God taken around one of them constitute a collective Child of God; this collective Child of God expresses also the Logos. Thus, the Logos is the manifestation of the fullness of God in and around every Child of God.

We infer also from the KCA that the Logos is the true nature of the Child of God. Therefore, the Child of God is in reality the good God expresses in him (the manifestation of the Logos) as he is the good God expresses around him (the manifestation of the Logos).

In ethics, this double nature translates into the fact that care for one’s self must necessarily imply care for the surrounding community. Now, this is the principle of ubuntu. Thus, like maât, ubuntu is a scientific, religious, and normative principle.

The Two Sources of Ethics in Bukôngo

Among the Kôngo people, the source of ethical norms can be religious or humanistic. This is seen in the fact that the Kôngo people have two words to traduce the idea of law: n’lôngo and n’siku. But, each word has its own connotation.

Fukiau (1969) sustains that the words longa (educate), n’lôngo (forbidden, sacred), kin’lôngo (sacred place), bun’lôngo (purity), an’lôngo (pure), n’lângu (water) and lôngo (marriage) are related.

To break the law, as n’lôngo, implies a breach of spiritual law, the fact of trespassing on the Logos, i.e., a violation of the purity (bun’lôngo) of the Child of God or of nature. Thus, n’lôngo is an offense against holy ancestors, ban’lôngo, the representatives of Nzâmbi Ampûngu Tulêndo, the Most High.

The breach necessary leads to a reprimand (béla) from the ancestors, reprimand which is the consequence of “béla, being wrong” for having walked contrary to sacred law. The final result of this offense can be a disease (bêla).

For the Besikôngo béla and bêla are not only homonymous, but also synonymous. Obviously the remedy for this situation includes the spiritual initiatory education (longa) whose corner stone is purification traditionally obtained through water (n’lângu).

On the other hand n’siku comes from the verb sika, i.e., to cause an explosion, a big noise. It can be said of a gun, n’kéle (sika n’kéle, to fire a gun), or of a traditional orchestra, sikulu (sika sikulu, to play music). N’siku is a norm relative to public order. To breach this norm (kulula n’siku, literary meaning to lower the n’siku, i.e., ethical norm) is to destroy the elevation of society.

In the conception of the Kôngo people, such an act must cause a public outcry (sika nkûzu); otherwise, the public is complicit of tin offense against public order.

It should be added that Contrary to the n’lôngo, the n’siku is established by a civil authority. The remedy for breaching a n’siku is to pay the fine, futa n’siku, or to undergo a tûmbu, a punishment established by the law.

The fact that in the mentality of Besikôngo, the Kôngo people, “kulula n’siku” (breaching the law) must necessarily lead to a public outcry, an explosion of indignation, shows that the public has a great responsibility in the maintenance of public order.

Therefore, contrary to the n’lôngo which denotes the religious aspect of the law, the n’siku is related to humanistic aspects of ethics in Kôngo society.

The ethical devolution of Black ethnics

We have seen in the previous shows that the migration of African ethnics from the north to the south of the Sahara has brought a religious devolution, i.e., the passage of the trends of ATR from the religion-exact-science nature to the religion-belief nature.

This religious devolution resulted in ethical devolution. By ethical devolution, we don’t mean a moral regression, but rather the displacement of the explanation of the ethical norm from the religious and humanistic line (as seen in Kôngo culture) to a totally humanistic line.

This can be realized as one makes a comparative study of the ethics of the Akan and that of the Kôngo people.

Comparative Ethics: the Akan and the Kôngo

In a paper titled African Ethics, the Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Gyekye studies the ethics of the Akan and explains it as being wholly humanistic. He writes about this ethics:

“Used normatively, the judgment, “he is a person,” means ‘he has a good character’, ‘he is generous’, ‘he is peaceful’, ‘he is humble,’ ‘he has respect for others.’ A profound appreciation of the high standards of the morality of an individual’s behavior would elicit the judgment, “he is truly a person,” (oye onipa paa!).”

One realizes the perfect similarity of this ethics with the ethics of ubuntu. This similarity led Gyekye to opine that the ethics of the Akan can be generalized to all the ethnics of Africa mutatis mutandis. Thus, according to the philosopher, African ethics is not religious, but wholly humanistic.

However, we have seen that the principles of maât and ubuntu have a religious explanation, and that the Kôngo ethics have both religious and humanistic origin. It results from this these facts that the Kôngo ethics cannot be explained from the Akan’s, while the reverse is possible mutatis mutandis.

This naturally leads us to the conclusion that the devolution of the traditional religion of the Akan, i.e., it passage from the religion-exact-science to the religion-belief nature has caused the confinement of the explanation of their ethics into the humanistic line.

Conclusion

In this era of globalization, it is imperious for Africans to understand the superior original nature of the ethics bequeathed to us by our ancestors. This ethics can be demonstrated to be based on religious and scientific values. Thus, contrary to the speculative downgrading ethical values of the West, the true ethics of Africa is a superior one.

However, the explanation of this ethics has been reduced to the humanistic line due to the devolution of the different trends of African traditional religion.

Therefore, it is important for Black people to understand the concept of ethical devolution in order to anchor our ethical norms back in their original superior religious and scientific bases.

References

- d. Maât notre ideal [Maât our ideal] http://fulele.unblog.fr/maat/

- Fukiau, A. 1969. Le Mukongo et le monde qui l’entourait [The Mukongo and the world that surrounded him]. Kinshasa: Office National de la Recherche et du Developpement.

- Gyekye, Kwame, African Ethics, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2011/entries/african-ethics/.

- Luyaluka, K. L. (2020) Bukôngo, available at amazon.com

- Luyaluka, K.L. (2015) Theocentric Big-Bang cosmology. Available at amazon.com.

Download the first chapter of The Storytelling Series: Beginners’ Guide for Small Businesses & Content Creators by Obehi Ewanfoh.