Economics Of Marketing Of Cassava Derivatives (Flour, Garri And Chips) In Uzo-Uwani Local Government Area, Enugu State

Dr. Ikechi Agbugba | Contributor on Agribusiness Topics

Dr. Ani, S. O. and Dr. Ikechi Agbugba, Department of Agricultural& Applied Economics/Extension, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Abstract

The study examined the marketing of cassava derivatives in Uzo-Uwani LGA of Enugu State. The study specifically described the channel of marketing; identified the constraints associated with its processing and marketing; and determined the returns per naira on investment of its marketing.

Want to learn more about storytelling? Start by downloading the first chapter of The Storytelling Mastery.

Multi-stage sampling was used to select 120 respondents from 5 communities in the study area. Several constraints associated with the processing and marketing of cassava derivatives were identified. The return per naira on investment of the cassava derivatives was evaluated, and the analysis showed that flour was more profitable with a profit of 9kobo per ₦1 invested in the business as against 7.8kobo and 7.1 kobo for garri and chips.

However, in order to increase the processing of cassava in Uzo-Uwani, it is recommended that the processors in the study area should be assisted by the government of Nigeria and private sector with credit facilities, processing facilities, good transportation network and storage facilities as this will go a long way to ease the effect of the constraints of the processors and marketers.

Keywords: Marketing, cassava, derivatives, processing, Nigeria

Introduction

Cassava is one of the world’s most important food crops with an annual output of over 34 million tons of tuberous roots (Food and Agricultural Organisation Database, 2005). Cassava production has been increasing for the past 20 or more years in area cultivated and in yield per hectare.

On average, the harvested land area was over 80 per cent higher during 1990–1993 than during 1974–1977 (Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 2006; Ope-Ewe, Adetunji, Kafiya, Onadipe, Awoyale, Alenkhe, & Sanni, 2011; Morgera, Caro & Durán, 2012). Throughout the tropics, its roots and leaves provide essential calories and income.

Africa is one of the continents of the world where some 600 million people are dependent on cassava for food (International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2013). According to Moya (2008), cassava is produced largely by small-scale farmers using rudimentary implements. The average landholding is less than two hectares and for most farmers’ land and family labor remain the essential inputs.

The land is held on a communal basis, inherited or rented; cases of outright 46 purchase of land are rare. Capital is a major limitation in agriculture; only a few farmers have access to rural credit. Almost all the cassava produced is used for human consumption and less than 5 percent is used in industries.

However, it should be noted that cassava per capita consumption is very high and provides about 80 percent of the total energy intake of many Nigerians (Ani, 2010). As a food crop, cassava fits well into the farming systems of the smallholder farmers in Nigeria because it is available all year round, thus providing household food security.

Compared to grains, cassava is more tolerant to low soil fertility and more resistant to drought, pests and diseases (Obisesan, 2012).

Nigeria is the largest producer of cassava tubers in the world with average annual production of about 35 million MT over the last 5 years. Cassava roots store well in the ground for months after maturity (Ope-Ewe et al., 2011). Its production industry in Nigeria is increasing at 3% every year but Nigeria continues to import starch, flour, and sweeteners that can be made from cassava.

This paradox is due to how cassava is produced, processed, marketed, and consumed in Nigeria, in a largely subsistence to semi-commercial manner. About one-third of the total national output comes from the Niger Delta region where many livelihoods depend on cassava as a main source of food and income.

See also Dr. Ikechi Agbugba at The House of Lords, The Palace of Westminster Abbey for Global Transformation

It has been estimated that the number of small commercially oriented cassava producers within the region would be in the range of 70,000- 120,000 (out of the more than 1 million producers) and over 400-500 cooperatives and cottage industries, 800,000-950,000 traders, 46 small medium processing industries and 1 large processing industry in the region (Nigeria Bureau of Statistics, 2008; Cassava Report Final, 2013).

Apart from livestock feeds, processed cassava serves as industrial raw material for the production of adhesives bakery products, dextrin, dextrose glucose, lactose and sucrose. Dextrin is used as a binding agent in the paper and packing industry and adhesive in cardboard, plywood and veneer binding.

Food and beverage industries use cassava products derivatives in the production of jelly caramel and chewing gum, pharmaceutical and chemical industries also use cassava alcohol (ethanol) in the production of cosmetics and drugs. The products also find ready use in the manufacture of dry cells, textiles and school chalk etc.

Cassava cubes are used mainly in the compounding of livestock feeds. Thus, there is a very high demand for cassava products in both local and export markets (AdulAzeez, 2013; Foundation for Partnership Initiatives in the Niger Delta, Foundation for Partnership Initiatives in the Niger Delta, PIND, 2011).

In Nigeria, cassava has moved from a food crop to a cash crop produced on an industrial scale and even exported (Obisesan, 2013). The introduction of new high-yield cassava varieties and improved farming techniques has led to a boom in production. Success is often said to bring new challenges. Cassava is one of the major sources of energy and the multiplicity of its use makes it indispensable for food security.

Several constraints affect cassava processing which limit the contribution that the crop makes to the nation’s economy. According to FAO (2011), cassava is important, not just as a food crop but even more so as a major source of cash income for producing households. As a cash crop, cassava generates cash income for the largest number of households, in comparison with other staples, contributing positively to poverty alleviation with other staples, contributing positively to poverty alleviation (Rural Sector Enhancement Programme, 2002).

As a food crop, cassava fits well into the farming systems of the smallholder farmers in Nigeria because it is available all year round, thus providing household food security. Hence, efficiency in cassava marketing is an important determinant of both consumers’ living costs and producers’ income and the potential of cassava marketing for agricultural and overall economic development cannot be overemphasized (Obisesan, 2012).

See also Learn About Business Storytelling with Obehi Ewanfoh: Testimonial from Dr. Ikechi Agbugba

Bissdorf (2009) observed that in some countries, there are already contractual arrangements between producers and processors for its supply. However, the growth in cassava production in Nigeria has been primarily due to rapid population growth, large internal market demand, complemented by the availability of high-yielding improved varieties of cassava, a relatively well-developed market access infrastructure, the existence of improved processing technology and a well-organized internal market structure (Onyinbo, Damisa & Ugbabe, 2011). The Federal

The government’s policy of including cassava flour in bread and other confectioneries to substitute wheat flour has presented great opportunities for investors and farmers alike. Basic tools used in garri are also used in flour production.

However, several constraints affect cassava processing which limit the contribution of the crop to the development of Nigeria’s economy (Adebayo & Sangosina, 2005; Ntawuruhunga, 2010).

Industrial utilization of cassava products is increasing but this accounts for less than 5% of the total production (PIND, 2011). However, simply boosting production without proper boosting of its marketing can lead to a glut of cassava on the market.

This can depress prices and discourage farmers from investing in and cultivating this fundamental crop (IFAD, 2013). Marketing can pose a problem for poor farmers who may not have the resources to transport their commodities to the market, especially those living in villages with poor feeder roads.

Typically, farmers transport their farm produce to the market on heads as head loads, on bicycles, or in lorries. With poor market access, the marketing of cassava can be particularly problematic because of its bulky nature, especially if it is not processed (Cassava Report Final, 2013).

Products derived from cassava include garri, starch, tapioca, fufu, pellets, flour, and chips. It has been eaten for centuries in various ways by indigenous people and continues to be a staple in local diets. The freshly harvested boiled tubers are eaten as the main starch at a meal, added to soups, used as a base for other dishes or fried as chips or snack crisps (Titus, Lawrence, and Seesahai, 2011).

Nweke (2004) survey of cassava utilization found out that 70%, 15%, 10% and 5%5%, 10%, and 5% of farmers respectively make garri, starch, fufu and tapioca from cassava. However, this paper concentrated on products derived from cassava roots which are: garri, chips, and flour. Garri is a cassava derivative that is described as cream white granular flour with a slightly fermented and slightly sour taste made from fermented gelatinized fried cassava tubers.

It processing involves certain units of operation. Cassava chips are another product from cassava, which is widely consumed in the South-eastern part of Nigeria. The chips can either be consumed after it has been sliced and left to ferment for a few days or consumed after a mixture of palm oil, some amount of spices, and vegetables.

See also Celebrating a Decade of Transformation – Dr. Ikechi Agbugba’s Thanksgiving Webinar

Cassava flour is yet another derivative that results after cassava chips are ground and either used for mixing fufu or used in bakeries as flour in making bread and other snacks for consumption (Federal Government of Nigeria/United Nations Industrial

Development Organization, 2006; Azih, 2008). The increase in the processing, marketing and consumption of cassava products means that there are increased marketing opportunities for farmers (Titus et al., 2011).

Cassava is produced mostly by smallholder farmers on marginal or sub-marginal lands of the humid and sub-humid tropics (FAO, 2002). Such smallholder agricultural systems as well as other aspects of their production and use often create problems, including the:

- Unreliability Of Supply,

- Uneven Quality Of Products,

- Low Producer Prices,

- And An Often Costly Marketing Structure.

The small-holder production system also implies that producers cannot bear much of the risk associated with the development of new products and markets.

Thus, the challenge is to create a strategy that affects production, processing, and marketing in such a way that they provide an array of high-quality products at reasonable prices for the consumer, while still returning a good profit for the producers without requiring them to assume the largest part of the development risk (Ntawuruhunga, 2010).

Purpose of the Study

The general purpose of the study is to economically analyze the marketing of cassava derivatives in Uzo-Uwani Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria.

Specifically, the purpose of the study is to:

- describe the channel of marketing of the cassava derivatives;

- determine the returns per naira on investment of marketing of the cassava derivatives; and

- identify the constraints associated with processing and marketing of the

cassava derivatives.

Materials And Methods

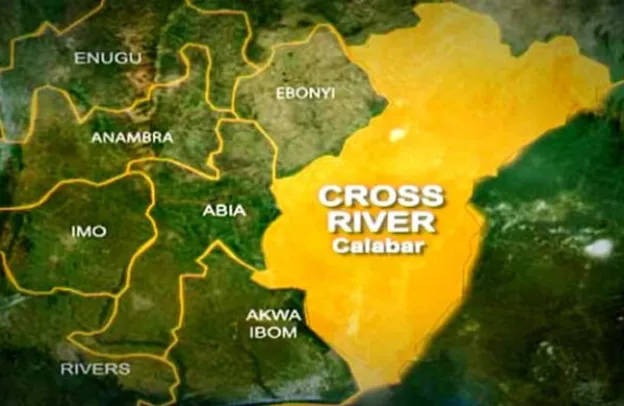

The study was conducted in a community in Enugu state, Southeast Nigeria. The community is made up of three (3) clans,

Igboda, Mbanano, and Ogboli, which comprise of sixteen (16) autonomous communities. It has a land area of 136.96 km2 and a population size of 124,480 persons (National Population Commission, 2006). The area lies within longitudes 6045/ and 70 North, and latitudes 7012/ and 360 East (Uzo-Uwani Local Government Bulletin, 1990).

There are primary feeder and terminal markets. The inhabitants are predominantly farmers. This could be as a result of the natural endowment of a large expanse of fertile agricultural land.

Multi-stage sampling was used to select the respondents in the study area. In stage I, a purposive selection of two clans on the basis of the area predominantly involved in cassava

processing. In stage II, five communities were randomly selected from each of the two clans selected in the first stage. In stage III, a census and listing of the cassava processors, as well as the marketers in each of the communities.

This exercise was conducted with the aid of the Enugu State Agricultural Development Program (ENADEP) officials, market associations, and community leaders. From the formed sampling frame, 24 respondents (12 processors and 12 marketers) were selected from each of the five communities. This gave a total of 120 respondents.

Primary data was used for the study. Well-structured questionnaire was used to collect information on the quantity of cassava that was used, conversion factors, cost of processing of the cassava, method of processing cassava, the cost of cassava that was used, and its returns. Descriptive statistics such as the use of diagrams, tables, percentages, and frequencies were used to analyze cassava-derivative marketing channels, as well as the constraints associated with their processing and marketing.

See also Agribusiness And Its Importance In Today’s Economy with Dr Ikechi Agbugba

The rate of returns per naira on investment was used to analyze the returns on investment of marketing of the selected cassava derivatives.

2.2.1 Rate of Return on Investment (RRI)

The formula can expressed as = Net Income

(NI) Total Cost (TC)

The Net Income was substituted by using the formula below:

N I = TR-TC

TC =Total cost of cassava derivatives

TR =Total revenue from the cassava derivatives aforementioned

TFC =Total fixed cost

TVC = Total variable cost

TC = Total Variable Cost (TVC) + Depreciation

Depreciation = Total Cost of assets – Salvage

value Useful life

Results

| enterprise include: cost of fresh tuber, cost stares, and frying spoons. The straight-line of transportation, cost of firewood, and cost of palm method was used in calculating the depreciated oil, total cost which are frying pans, sieves, and values of the equipment used. The results are machetes, sack bags, knives, basins, and wooden indicated in Table 1. Table 1. Returns per Naira on Investment of Processing ₦10,000 Worth of Cassava Tubers (5000kg) to the Cassava Derivatives |

Source: Field Survey, 2010

Results indicate that 500kg of cassava tubers was used to produce garri which costs about ₦10,000 at average price of ₦250 per kg. The labor cost was ₦4,400; s the depreciation of the equipment used was ₦850 giving a total cost of ₦17,550. The total revenue was ₦31,200, while the profit was ₦13,350.

For chips processing, ₦10,000 (5000kg) worth of cassava tubers was processed into chips at the average price of ₦250 per kg with the labor cost of ₦4,600 and depreciation of equipment used at ₦1,180. The total cost incurred by the processors was ₦17,500 with total revenue of ₦30,000. The processor made a profit of ₦12,500.

On the other hand, in flour processing, the table showed that ₦10,000 (5000kg) worth of cassava tuber was used to produce cassava flour at the average price of ₦250 per kg. The respondent incurred a depreciation of ₦925. The total cost was ₦30,500, while the profit was ₦14,425. The survey also.

indicated that labor cost and cassava tuber constituted the highest amount spent in the processing business, while the depreciation cost was the least. The return per naira of investment on the processing of ₦10,000 worth of cassava tuber into different derivatives gave 7.8 kobo for garri, 9 kobo for flour and 7.1 kobo for chips.

This implied that for every ₦1 invested in garri, flour and chip processing, it yielded the sum of 7.8 kobo, 9 kobo and 7.1 kobo respectively.

Constraints encountered in Processing of Cassava Derivatives Cassava processing and its marketing are faced with a lot of bottlenecks that limit the ability of the processors to improve their processing activities; reduce their level of participation and marketing of products; and consequently, retard the expansion on investment on the processing business. Table 2

| Table 2: Distribution of Respondents by Constraints of Cassava Processing |

summarizes the results Source: Field Survey, 2010

Discussion

Description of Cassava Marketing Channel

The marketing channel for the marketing channel of the cassava derivative was rightfully identified. Channel comparison for the Cassava derivatives was also done based on the multiple responses of the marketers.

Percentages were used to denote these responses as the products pass through each of the channels from the cassava processors to the final consumers. A similar observation was made by Ani et al. (2013) and Onya et al. (2016) in their findings on the marketing of cassava product and market participation and Value Chain of Cassava Farmers, respectively.

Return per ₦10,000 Investment in Marketing of the Cassava Derivatives

As the results in Table 1 indicate, the profits wielded by the garri and chips processors concurred that the enterprise is highly profitable. This therefore, supports that cassava processing has pivoted to be a veritable occupation that can lift a lot of rural processors out of the pit of poverty with their returns on investment like no other.

It therefore offers an important entry point for cassava processors providing an important entry point for their livelihood to be supported. Nwafor et al. (2016) in their study on the impact of returns from cassava production and processing in Abia State, made a similar observation. However, from the result it is interpreted that cassava processing business is worth embarking upon based on the result from the return per naira of investment.

The returns on per naira invested in the processing of cassava tuber into different derivatives gave reasonable monetary rewards. Furthermore, it is interpreted that cassava processing enterprise is worth embarking upon based on the result from the return per naira of investment. Also, various economic analysis carried out by researchers have indicated that cassava processing is a profitable business venture.

Similarly, the findings of Muhammad Lawal et al. (2013) and Oni (2016) on the economics of cassava processing in Kwara State and socio-economic determinants and profitability of cassava enterprise, respectively agrees with the findings made. In view of this, the cassava farmers were advised to invest more cash in flour processing business in the study area.

Constraints Associated with the Processing and Marketing of Cassava Derivatives

From the findings of the study, the major constraints to cassava processing and marketing includes: inadequate finance, lack of processing facilities, high of labour, marketing problems (such as poor infrastructure), high of transportation and inadequate storage facilities.

This finding clearly supports the findings of Akinnagbe (2010); and Rahman and Awerije (2016) in their studies on the constraints and strategies towards improving cassava processing in Enugu State and exploring the potential of cassava in promoting agricultural growth in Nigeria, respectively.

Recommendations

Government as well as private sectors’ indispensable role in the study area in providing cassava processors access to resources needed to acquire and maintain innovations cannot be over emphasized. Credit facilities, appropriate energy sources and trained personnel should be made available within reach to processors and marketers of cassava and its derivatives.

The Federal Government of Nigeria should identify and create widespread national awareness of the alternative industrial and non-food uses of cassava through advertisement in electronic and all relevant media awareness creation through trade fares and other interaction.

Finally, market opportunities can be fully developed through provision of adequate infrastructures such as good roads, pipe borne water, modern market and processing centres, as well as efficient transport and communication system. Such development will boost both domestic and export market for gari, flour and chips as well as other processed cassava products.

Conclusion

The processing of cassava into the derivatives has proven to be a veritable occupation that can lift a lot of cassava processors out of the pit of poverty; the return on investment is like no other. In other words, findings from the study showed that the increase in the economic activities of cassava means an increase in the marketing opportunities for the farmers.

Hence, marketing of cassava derivatives (garri, chip and flour) is a profitable business venture in the study area.

The need therefore, arises to step up its processing and expand this industry as this will create greater opportunities for income generation for the rural populace, as well as achieve the target of the presidential initiative on cassava production and export. In other words, the enterprise should be encouraged by the government to use improved processing techniques which eliminates drudgery, wastefulness and low productivity associated with traditional processing.

See also Collaborations and Networking: How to Build a Creative Ecosystem That Can Fuel Your Business

References

Adebayo, K. and M.A. Sangosina (2005). Perception of the effectiveness of some cassava processing innovation in Ogun

State, Proceedings of 19th Annual conference of Farm Management Association of Nigeria held at Delta State University, Asaba Campus 18th–20th October, 2005, pp 234-235.

Akinnagbe O.M. (2010). Constraints and Strategies towards Improving Cassava Production and Processing in Enugu North Agricultural Zone of Enugu State, Nigeria, Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Research. 35 (3): 387-394.

Ani, S.O. (2010). Comparative economic analysis of selected cassava derivatives in Uzo-Uwani Local Government Area of Enugu State, Unpublished M.Sc Research work, Department of Agricultural Economics University of Nigeria Nsukka, .

Azih, I. (2008). A background analysis of the Nigerian Agricultural Sector (1998-2007). Research Thesis for OXFAM Novib Economic Justice Campaign in Agriculture, Retrieved

reseaux.org/IMG/pdf_Final_Report_on_Bakgr ound_Analysis_of_Nigerian_Agric_ Sector_Oxfam_Novib_november_2008.pdf on 24/06/2013.

FAO (2013). Cassava Report Final Action Plan for a cassava transformation in Nigeria, retrieved from: www.unaab.edu.ng/attachments/Cassava%20 Report%20Final.pdf on 27/06/2013.FAO (2002).The state of food insecurity in the world.

FAO (2000). Food and Agricultural

Organization, United Nations, Rome, Italy.

FAOSTAT Database, 2005. FAO

(2011). Strengthening Capacity for Climate Change Adaptation in the Agriculture Sector in Ethiopia, Proceedings from National Workshop held in Nazreth, Ethiopia 5th-6th July, 2010, (Climate Change Forum, Ethiopia) organized by Climate, Energy and Tenure Division Natural Resources

Management and Environment Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome,

Italy.

Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources (2006). Cassava development in Nigeria: A country case study towards a global strategy for cassava development prepared by Department of Agriculture, Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Retrieved from: ftp://ftp. fao.org/docrep/fao /009/A0154E/A0154E02.pdf on

27/06/2013.

FGN/UNIDO (2006). Cassava Master Plan: a strategic action plan for the development of the Nigerian cassava industry. Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN)/ United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO).

Foundation for Partnership Initiatives in the Niger Delta, PIND (2011). A Report on cassava value-chain analysis in Niger Delta. Retrieved from www.pindfoundation.net/wpcontent/pluggins/Cassava–Value -ChainAnalysis.pdf on 26/06/2013.

Ibirogba, F. (2013).Cassava Production, Processing and Marketing; African

Newspapers of Nigeria Plc.,

African Newspapers of Nigeria Tuesday February 29th, 2013, Site designed by Tribune Web

Team. Retrieved from:

www.tribune.com.ng/news2013/en/component/ k2/item/4060–cassava production–processingand– marketing.html on 27/06/2013.

International Fund for Agricultural Development, (2013). Cassava: turning a subsistence crop into a cash crop in Western and Central Africa, Rural poverty portal, Breadcrumbs Portlet, powered by IFAD.

Rerieved from: http://www.fidafrique.net/rubrique554.html on 27/06/2013.

Muhammad-Lawal A., Omotesho O.A. and

F.A. Oyedemi (2013). An Assessment of the Economics of Cassava Processing in Kwara Stat, Nigeria, Invited paper presented at the 4th International Conference of the African Association of Agricultural Economists, September 22-25, 2013, Hammamet, Tunisia.

Morgera, E., Caro, C.B. and G.M. Durán (2012). Organic agriculture and the law for the Development Law Service, FAO Legal Office 107, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2012.

Moya, S. (2008). African Land Questions, Agrarian Transitions and the State, Council for the Development of Social Sciences Research in Africa, CODESRIA working paper series, Imprimerie Graphiplus, Dakar Senegal.

National Population Commission (2006).Population Figures, NPC, Abuja FCT. National Technical Working Group (2009). Agriculture & Food Security, Report of the

Vision 2020. Retrieved from:

www.npc.gov.ng/vault/NTWG%20Final%20R eport/energy%20ntwg%20report. pdfon 27/06/2013.

Ntawuruhunga, P. (2010). Strategies, choices, and program, Priorities for the Eastern African Root Crops Research Network, EARRNET Coordination office, IITA Uganda.

Nweke, F.I. (2004).New challenges in the cassava transformation in Nigeria and Ghana. Environment and Production Technology Division. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Washington, USA.

Obisesan, A.A. (2013). Credit Accessibility and Poverty among Smallholder Cassava Farming Households in South West, Nigeria, Greener Journal of Agricultural Sciences, Vol. 3 (2), pp. 120-127.

Oni T.O. (2016). Socio-economic determinants and profitability of cassava production in Nigeria, International Journal of Agricultural Economics and Extension, 4 (4), 229 – 249.

Onya S.C., Oriala SE, Ejiba I.V. and Okoronkwo F.C. (2016). Market

Participation and Value Chain of Cassava Farmers in Abia State, Journal of Scientific Research and Reports, 12(1): 1-11.

Onyinbo, O. Damisa, M.A and O.O. Ugbabe, (2011). An assessment of the profitability of small-scale cassava production in Edo state:

A Guide to Policy, Retrieved from: www.academia.edu/1995/

84_/AN_ASSESSMENT_OF_THE_PROFITABIL

ITY_OF_SMALL_SCALE_CASSAVA_PROD

UCTION_IN_EDO_STATE A_GUIDE_TO_POLICY. Assessed on

28/06/2013.

Ope-Ewe, O.B., Adetunji, M.O. Kafiya,M.R., Onadipe, O.O., Awoyale, W., Alenkhe, B.E. & Sanni, L.O. (2011). Cassava value chain

development by supporting Processing and value Addition by Small and Medium Enterprises in West Africa- Nigeria. Technical Report August 2008 – August 2011.

Rahman S. and B.O. Awerije (2016). Exploring the potential of cassava in promoting agricultural growth in Nigeria, Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 117, 1 (2016) 149–163

Titus, P., Lawrence, J. and A. Seesahai (2011). commercial Cassava Production, Technical Bulletin, CARDI, Issue 5/2011. Available online at: www.cardi.org. Retieved 5/5/2017.

Uzo-Uwani Local Government Area Bulletin (1990). Umulokpa, Uzo-Uwani, Enugu State.

Want to learn more about storytelling? Start by downloading the first chapter of The Storytelling Mastery.