Racism And Slavery: How The Hamitic Theory Began To Crumble

This is part three in the series “Racism And Slavery: Reflection On Human Madness by Stefano Anselmo”. See part one to learn more.

Want to learn more about storytelling? Start by downloading the first chapter of The Storytelling Mastery.

Here is a list of all the articles in the series – Racism And Slavery: Reflection On Human Madness by Stefano Anselmo:

- Racism And Slavery: Reflection On Human Madness by Stefano Anselmo

- What Racism Requires: Religion And Science Were To Go Hand In Hand

- Racism And Slavery: How The Hamitic Theory Began To Crumble

- In America Before Columbus: Exploring European Racist Stereotypes

- Racism And Slavery: African Crisis Is An Invention Of The West

- Our House Slaves: European Centuries Of Heritage

- Religious Endorsement Of Slavery As A Legitimized Business Both In Islam And Christianity

What is The Hamitic Theory?

The Hamitic Theory was a now-discredited historical and anthropological theory that gained prominence in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It proposed a racial hierarchy within the African continent, placing the Hamitic people at the top. According to this theory, the Hamites were believed to be a superior race, both culturally and intellectually, compared to other African groups.

The term “Hamitic” is derived from Ham, one of the sons of Noah in the biblical narrative. In the Old Testament, Ham is often associated with the biblical figure cursed by his father Noah, leading to interpretations that linked the descendants of Ham with servitude and inferiority.

Proponents of the Hamitic Theory believed that the Hamites were responsible for many of the advanced civilizations in Africa, including Ancient Egypt, Ethiopia, and other civilizations around the Nile River. They argued that these civilizations were too sophisticated to have been created by indigenous African peoples, and thus must have been the result of migration or influence from outside the continent.

This theory served to justify European colonialism and imperialism in Africa by portraying Africans as backward and in need of European “civilizing” influence. It was used to rationalize the exploitation and subjugation of African peoples, as well as to support policies of segregation and discrimination.

However, the Hamitic Theory has been widely discredited by modern scholarship. There is no evidence to support the notion of a distinct “Hamitic” race, and archaeological and genetic research has shown that many of Africa’s ancient civilizations were indeed indigenous developments.

The theory is now recognized as a product of racist ideologies and colonialist agendas, and its influence has largely faded in academic circles. With that clarified, let’s now continue with the series:

Continuation Of The Series

The invention of the Hamitic race For a long time, black people were discriminated against and considered incapable and inferior until, with Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt (1798), it was discovered that Africans had produced a great civilization, a stark contrast to previous claims.

The impressive findings sparked a lively scientific debate on the origin, the level of civilization reached by the Egyptians, and their potential contacts with other populations of the continent. Napoleon’s scientists agreed that the beginning of civilization could be traced to Egypt, before the Greek and Roman eras.

The Hamitic theory began to crumble: how could black people have created such a high-level civilization? Exegetes got to work and, re-examining the Bible found the answer that reconciled science and religion.

In Genesis, it’s Canaan’s lineage, Cam’s youngest son, that is cursed, not Cush, Mizraym, and Put, who, not being cursed, could have produced civilizations. Thus, a new conception of the human category emerged: the Hamites, also called negroids or fake blacks; people who, in appearance and color, resembled black Africans but were “white” on the inside.

Therefore, the Egyptians, defined as “non-black,” were seen as relatives of white Europeans, and with the term Hamite, all scholars sought to create a demarcation line between Africans close to the European stock and the “true blacks.”

In other words, those black peoples who produced civilizations did so because they came into contact with foreign non-African cultures. Later, even the news of visitors venturing towards the Niger and the Upper Nile and reporting on peoples who had nothing to do with the image of the inept and limited African complicated matters even more.

It was also the undeniable ability of some people and, not least, their elegant appearance, different from other blacks, a fact to which Westerners could not provide a “scientific” answer that was not in conflict with biblical texts.

Without forgetting that by the mid-19th century, racial classification had already shown all its weaknesses: the number of races had increased exponentially, and no one could affirm with certainty how many or which ones there were because their boundaries were increasingly tangled.

The solution to the conflict between facts and imagination was easily found by sacrificing the former. In other words, if the congenitally inept “Blacks” at creating civilizations had devised such societies, it meant that, contrary to appearances, they were not “Blacks” in every respect.

Thus, the Hamitic myth was resumed, which effectively fulfilled the effort to persuade European intellectuals and African elites about the division into two categories of the inhabitants of the Great Lakes region: the first, that of “authentic Blacks,” indigenous, repositories of the most classic and widespread European prejudices among which were the Hutu and Twa, and the other, that of “fake Blacks,” foreign-origin civilizers, also known as “originally white Blacks” of Asian origin, those who dominated and civilized the Great Lakes region.

In this way, the legacy of 18th-century Natural Sciences, which imposed classification and labeling, was satisfied.

In his famous travel diary, John Hanning Speke tries to explain the level of civilization reached by the peoples of the Great Lakes by contributing to the spread of the Hamitic hypothesis in these areas: the societies of present-day Uganda, the western shore of Lake Victoria, Rwanda, and Burundi were more advanced thanks to foreign infiltrations of Asian origin.

Thus the Tutsis were recognized as people of Hamitic origin while the Hutu and Twa were considered Bantu, true Africans less human, and true Rwandans. The Tutsi aristocracy led a state so sophisticated that it could only be native to a geographically and culturally, and above all, racially, “close” region to Europe, such as Ethiopia, a country that had been “Christianized” for many centuries.

The French exegete August Knobel, for example, speaking of the Tutsis, explains that although they are dark-skinned, they belong, like the Japhetites and Semites, to the great Caucasian class: blacks are a completely different human race.

Particularly illustrative is the text by Charles Seligman reprinted several times from the ’30s to the ’60s: “The civilizations of Africa are Hamitic civilizations (…) The Hamitic invaders were Caucasian shepherds, arrived in waves, armed with better weapons and greater intelligence than the black farmers with dark skin (…)”.

See also The Origin Of Uromi And Esanland, Nigeria (Agba: The Esan God Of War, 1)

Here various authors began to see in the Fang a Germanic component, in the Zulu the descendants of the Sumerians, in the Fulani Judeo-Syrians of antiquity, in the Ethiopian Galla the descendants of a Gallic incursion, in Great Zimbabwe a Phoenician residence, in Nigerian Ife statuary clear signs of Hellenic school, and in the Tutsis, Ethiopian or even pharaonic and therefore white origins.

According to others, the Tutsis would have come from Asia Minor passing through Egypt, populating Abyssinia, gradually pushing south to Rwanda; according to others, even from Atlantis.

It must not be forgotten that behind every statement about the Aryan or non-blackness of a people, there was implicitly and automatically decreed belonging to a superior race and its “natural” right to command and supremacy over those considered inferior.

When Europeans went to Africa, they encountered radically different cultures that were largely incomprehensible. Africans then were “guilty” of being too different in customs and especially in appearance: a world that for centuries continuously celebrated powder and ceruse to whiten skin and hair was unable to “see” beyond the blackness of African skin.

Soon, through a series of mechanisms, an answer was found to this diversity by classifying them as another race, different and inferior. Already in the 17th century, denigrating the appearance of Blacks, Winckelmann said of the ancient Egyptians: “How can one find even a glimmer of beauty in their figures, when almost all the originals they (the Egyptian representations, Ed.) were inspired by have the forms of Africans? That is, they had, like themselves, full lips, small and elusive minds, flat and hollow profiles (…) they often had flat noses and dark complexions…”

The image of the African as a “degenerate being” remained persistent throughout the Middle Ages and was almost universally accepted until the 1600s. Only during the Enlightenment with monogenist and polygenist theories, were these hypotheses questioned.

Many men of thought described the origin of the “Negro” according to two different theories: for the monogenist theory, it was the result of degeneration due to environmental conditions, thus attempting to explain its physical characteristics through nature. For the polygenist theory, it was simply a separate and subhuman creature.

During the Enlightenment, many scientists and scholars contributed to spreading the theory of races, making it a “scientific reality” essential to justify Africa’s backwardness and the “right” supremacy of the white race over the black one, in perfect line with the Holy Scriptures.

In 1761, the naturalist J.B. Robinet created a racial scale where the Negro is placed in a position slightly superior to animals, and the European stands at the head of evolution; between them, there is the Hottentot, already fully human but still stupid and uneducable, the Lapp, the Asian, the Tartar, the Chinese, the Indian, and the Persian.

The naturalist Petrus Camper (1722-1789) built a “Science of race” based on the objective revelation of the facial angle, that is, the inclination of the profile. Even in this case, there is a gradual transition from the 40° of a monkey with a tail to the 58° of an Orangutan, to the 70° of a Negro, to the 80-90° of a European, up to the 100° of the Greek type, the perfect and definitive model of the Human Being.

According to this theory, the “percentage” of humanity could be mathematically determined: from the 100° of the Hellenic man to the group that is below 70°, and that is the monkey, the dog, and other animals, up to the bird, whose facial angle is almost equal to zero.

Others joined this new science: Charles White (1795) illustrates, according to the inclination of the facial angle, the continuity between the monkey and civilized man, and in 1799, he published on this subject the text of a conference held at the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester, An Account of the Regular Gradation of Man, and in Different Animals and Vegetables; the naturalist Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741 – 1801) supported a direct link between man and the frog, once again measurable through the inclination of the profile.

Obviously, this way of classifying human types has no scientific basis. In fact, while the prognathic profile is characteristic of some sub-Saharan blacks, it is equally true that the straight profile does not guarantee any Caucasoid, as can be seen in illustration No. 3, where the three African profiles on the right have the same inclination as the European one on the left, if not even lower.

However, these theories favored the idea that the African was a sub-human, more animal than anything else, a kind of nature’s distraction, and, with the support of the Sacred Scriptures, could be treated as such without committing any sin. Throughout the 19th century and much of the 20th, racism was an expression of science; thus arose “Scientific Racism.”

Joseph A. Gobineau’s “Essay on the Inequality of Human Races,” still considered one of the first examples of Scientific Racism, significantly contributed to the spread of Hamitic theories. In short, Gobineau argues the existence of irreconcilable differences between human races, that civilization declines when “races” mix, and that the Caucasian Europoid (white man) is superior to others.

These ideas found easy and widespread acceptance in the United States and German-speaking countries and to a lesser extent in France. The German historian Joachim Fest, author of Hitler’s biography, writes: “Significantly, Hitler simplifies Gobineau’s elaborate doctrine to make it demagogically usable and thus offer a series of plausible explanations for all the dissatisfactions, anxieties, and crises of the contemporary scene.

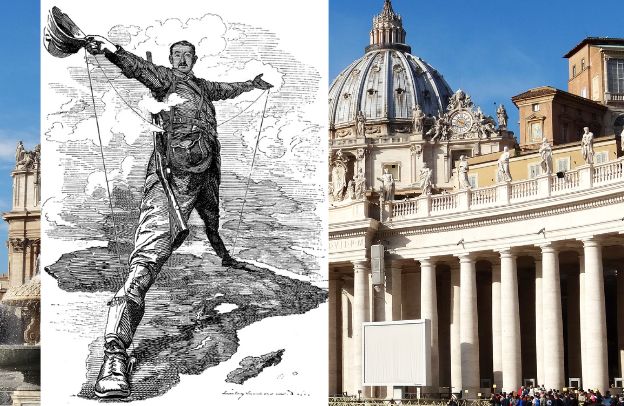

Denigrating Blacks To denigrate the figure of the African, thus justifying colonial oppression, highly irreverent caricatures were disseminated, and widely spread at the time, so much so that they were sold even in tobacco shops. These illustrations, mostly advertising, always portrayed him as the antithesis of the Greek-Aryan aesthetic ideal of Greek statuary, elevated to the absolute model of perfection.

See also Arikana Chihombori-Quao: Champion of African Unity, Diaspora Engagement, and Economic Empowerment

Often, they were advertisements for soaps where their cleansing property was exalted by whitening an African, thus conveying the idea that his skin was dark because it was dirty. Not of secondary importance were the methods to dehumanize them and favor a bestial type of vision.

For a long time in the West, denigration and mockery went hand in hand with racial discrimination. Men and women forcibly deported were exhibited in zoos and circuses (figs. 6,7 and 8) as shown by the postcard whose caption reads: “Zizi and his mother” where the mother of the chimpanzee is an African, or the Congolese pygmy Ota Benga, displayed with bows and arrows in New York in the monkey cage. Africans, locked in cages, often dressed as savages, had to emit beastly screams and eat raw meat to attract the public’s attention.

Defamatory strategies to dehumanize African Blacks drew on everything that could be useful to support racist theories: popular beliefs, history, and religion, both appropriately readapted for their own use and consumption:

Curse of God upon the black people (Shem, Ham, Canaan) +

- Lack of civilization (Africa has not produced civilization) +

- Lack of history (Africa does not have a true history like Europe) +

- Probably soulless like women (according to medieval scholars’ discussions) +

- Non-Christians: pagans or of other religions = It’s not so serious to enslave inferior beings more similar to animals than humans.

One of the many: the Congolese pygmy Ota Benga End of the 19th century: in the Belgian Congo, a “personal” possession of King Leopold II of Belgium, Ota Benga is captured by the Belgian Force Publique, sold, and taken to Saint Louis and then to the zoo in New York.

In front of his cage, a sign explains: “Ota Benga, African Pygmy.” Ota attracts thousands of people. Visitors mock him, harass him, throw objects and food at him, and force him to smile constantly to show off his filed teeth, as per the Pygmy tradition. He endures it, and when he can’t take it anymore, with the bow provided to make him seem more wild, he starts shooting arrows at the audience.

A Baptist pastor takes him into custody and tries to Americanize him, attempting to teach him English and having his teeth capped. Employed in a factory, he works to save money for his return to Africa. But the Great War breaks out, and he cannot pursue his plan. He falls into depression and commits suicide, making two gestures that speak volumes: he removes the caps from his teeth and lights a ceremonial fire. Then he shoots himself.

The formula of discrediting implemented to justify otherwise considered immoral actions and attitudes was reiterated several times, applying it whenever the opportunity or necessity arose: savage, uncultured Africans incapable of producing art and civilization needed to be educated, and it was fair to economically compensate the effort by tapping into the abundant human and natural resources in Africa.

In line with this way of acting, there was a tendency to deny the indigenous origin of valuable works with the “certainty” that Africans were not capable of making them, attributing their paternity to other white peoples.

All this was in perfect line with the theory of the conqueror Rhodes (from which the old name Rhodesia, the current Zimbabwe, derives), according to whom Africans could not have been able to create a civilization important enough to build the Great Zimbabwe with large walls built with a grandiose technique in conception, which has no parallels in the rest of Africa or in other continents.

See also Decolonizing the African Curriculum: Empowering Voices, Challenging Biases

To build the fortresses dating back to the 5th-6th centuries, indeed, blocks of stone weighing a ton were used, and arranged to create a complex decorative effect. Only much later did science, with sophisticated investigative techniques, pronounce that these were constructions made by indigenous Africans.

However, books spreading Rhodes’ theories were printed and read for many decades; thus, in the minds of most, the inferiority of Africans became an established fact.

Conversely, some of these ancient cultures were so advanced as to have established trade relations with the Far East, it seems, since the late 9th century. Evidence of this can be found in the ruins of Zimbabwe, Lamu in Kenya, and Kilwa in Tanzania, city-states destroyed by the men of the Portuguese Vasco da Gama in the second half of the 15th century.

These ruins still show Chinese ceramics embedded in the mortar as architectural decoration. Other ceramics have emerged from excavations. Moreover, in China, there is a drawing, here on the right, of a giraffe brought by the traveler Zheng He, given by the king of Malindi to the Chinese emperor: we are just under a century before the discovery of America.

Want to learn more about storytelling? Start by downloading the first chapter of The Storytelling Mastery.