The Legacy of King James and the Unquestioned Reverence for Colonial Christianity in Africa

It’s a Sunday morning in Africa. You can almost feel the excitement in the air as thousands of people—dressed in their finest clothes—rush to their churches. Inside, a familiar scene unfolds: the sound of hymns echoing in grand cathedrals or in humble local spaces, where worshippers fervently await a savior. It is a moment of hope, reverence, and devotion. But have you ever paused to wonder: why does this devotion to Christianity, especially using the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, endure so strongly?

Want to learn more about storytelling? Start by downloading the first chapter of The Storytelling Mastery.

This isn’t just a question of faith, it’s a question of history, culture, and power. In fact, the African love for the King James Bible might tell you more about Africa’s past—and the enduring legacy of colonialism—than you think.

Today, many Africans still embrace the King James Bible as the definitive, sacred text. Yet, for some, the continued reverence of this particular translation raises a crucial question:

- Why do we still cling to the religious tools of our colonizers?

- Why is there such an emotional attachment to a Bible whose words, translated by Englishmen centuries ago, carry the cultural and political baggage of a colonial past?

Even among Pan-African scholars and activists—those who otherwise challenge Western oppression—there is a conspicuous silence on this subject. Could it be that the reverence for the King James Bible is a subtle form of continued mental colonization?

The Historical Roots: Christianity as a Tool of Empire

To understand why the King James Version of the Bible still holds such sway, it’s necessary to revisit the history of Christianity in Africa. European missionaries, often working hand in hand with colonial powers, introduced Christianity to Africa during the height of imperialism in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

You might also like The Vatican And European Imperialism – Moving Beyond The Shadows Of Colonialism In Africa

As noted in a Live Science article, “Why is the King James Bible so popular?” the enduring popularity of the King James Bible can be attributed to its widespread distribution and influence, particularly in English-speaking countries.

According to Gordon, the KJV remained largely unchallenged until the 20th century, becoming deeply ingrained in the Anglo-American world. Its reach extended far beyond Western borders, as Christian missionaries introduced the Bible to Africa and Asia, where many people learned English through its texts, further cementing its global legacy.

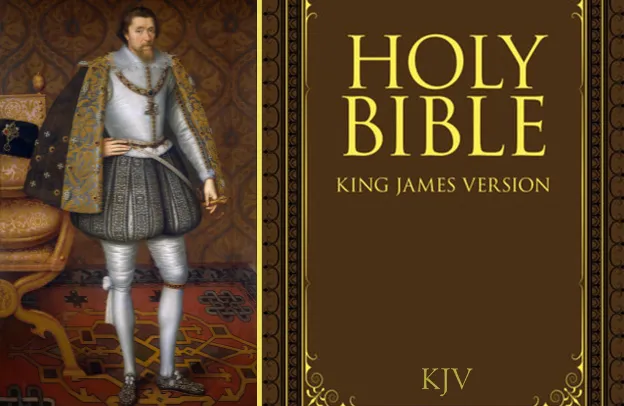

The King James Bible, published in 1611, was the standard text for these missionary endeavors. By the time European powers partitioned Africa at the Berlin Conference in 1884, the KJV had already become entrenched in the African consciousness.

Christianity in Africa wasn’t just a spiritual movement—it was an ideological one. Missionaries often saw themselves as the bearers of “civilization,” tasked with saving the “heathen” Africans from their so-called primitive ways.

The King James Bible, with its distinctly European flavor, was presented as the holy and only true word of God, reinforcing the idea that European religion was the only path to salvation and cultural progress.

During the colonial period, European powers aimed not only to control Africa politically and economically but also to dominate its culture. That was done through The Bible, the Gun, and the Anthropology as the primary tools of domination with each reinforcing the others in a powerful and insidious cycle.

The Bible justified the moral authority of European rule, the gun enforced physical control, and the anthropologist, often acting as a cultural intermediary, helped frame African societies as inferior, thus legitimizing colonial exploitation. Together, these instruments worked to reshape Africa’s identity, history, and worldview, securing Europe’s grip on the continent.

As different historians have explained, missionary education in Africa was designed to create a generation of “faithful subjects,” whose identities would be shaped by European ideals and whose loyalty to the colonial administration could be secured through the propagation of Christian values.

See also Nnamdi Azikiwe Speaks at a Rally for Nigerian Independence at Trafalgar Square, London 1949

Nigeria, like much of Africa, is deeply entrenched in religious divisions that could one day erupt into conflict. That is for another day. Southern Nigeria is flooded with churches on nearly every street, yet the country’s corrupt political elites seem to maintain a firm grip on power.

This is not coincidental because religion, since the days of European colonialism, has been strategically used to pacify the masses, keeping them docile and submissive to authorities who mismanage the nation’s resources. The promise of rewards in the afterlife has led many to place little value on holding political leaders accountable for their actions.

Consequently, there is little pressure on the elites, who continue to enjoy the country’s wealth while squandering it for their own gain. This pattern of religious manipulation and political exploitation is not unique to Nigeria but can be seen in many African countries, where religious institutions are often complicit in maintaining the status quo, to the detriment of the people.

The King James Version: A European Product with African Consequences

The King James Bible itself, though might be seen as a monumental achievement in Western religious literature, is inherently a product of European historical and political circumstances. It was translated by scholars under the patronage of King James I of England, whose main aim was to standardize Christian doctrine for his English-speaking subjects.

For African communities, the KJV became a symbol of authority—a text that could not be questioned. It became the medium through which African spirituality was redefined and stripped of indigenous practices and beliefs. Missionary schools taught children to recite verses in the KJV as part of their formal education, reinforcing not only Christianity but a Western view of knowledge and reality.

The issue isn’t just about the Bible itself—let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that it was created innocently, without any hidden agenda. The real question is: why would King James or the British monarch, a power that was complicit in the enslavement of Africans, be morally justified in offering a text that supposedly provides freedom to the same Africans? This doesn’t add up.

As Bob Marley famously said, “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery; none but ourselves can free our minds.” The truth is that the Bible, as it was disseminated during the colonial era, was often used as a tool of control rather than liberation. Shortly, we will delve deeper into the British monarch’s complicity in the transatlantic slave trade and explore the long-lasting impact of its colonial legacy.

Even after the end of formal colonial rule in the mid-20th century, the psychological impact of this religious imposition endured. The KJV, widely disseminated across Africa, continued to represent divine truth.

Now, this is how to know who truly rules over you. Look around to see who you are not allowed to criticize.

The British Kings and Queens and Their Role in Slavery

A recent article from The Guardian explores the extensive role British monarchs played in supporting and profiting from the transatlantic slave trade over a span of 270 years, from the reign of Elizabeth I to William IV.

The article, “The British kings and queens who supported and Profited from Slavery” highlights how twelve British monarchs were directly involved in slavery, either by financially supporting slave trading companies or granting monopolies that enabled the trade.

For example, Elizabeth I provided a royal ship to slave trader John Hawkins in 1564, while Charles II invested in the Company of Royal Adventurers, which later became the Royal African Company, the largest slave trader in history. Other monarchs, like James II and George I, were also major stakeholders in these companies, profiting immensely from the exploitation of enslaved African people.

Despite recent statements from King Charles III and Prince William expressing sorrow for the atrocities of slavery, neither has publicly acknowledged the monarchy’s central role in the trade.

The article details how monarchs like George III, who personally opposed the abolition movement, and William IV, who defended slavery as vital for prosperity, delayed the fight for emancipation. It also touches on how the British monarchy’s involvement in the slave trades a matter of moral failure was not only.

It was also one of immense financial gain, as monarchs profited from colonial ventures such as the South Sea Company, which transported thousands of enslaved Africans to the Americas. This legacy remains a key part of the monarchy’s history, with continuing debates about its acknowledgment and accountability today.

The True Intervention Of Europeans In Africa Is Economic

Africans must fully grasp the true intentions behind European actions on the continent, which have always been primarily driven by economic interests, rather than genuine concern for Africa’s well-being.

Whether under the guise of international aid, humanitarian programs, or peacekeeping missions, European powers have consistently sought to maintain their control over Africa’s resources and strategic positioning.

This is most evident in the aftermath of the Berlin Conference, where colonial powers carved up Africa with no regard for African sovereignty or cultural realities, all in the pursuit of economic exploitation.

More recently, euro-western military interventions, such as NATO’s involvement in Libya, underscore this continued pattern: the intervention was framed as a humanitarian effort, but in reality, it served Western interests in securing access to oil and maintaining influence in the region.

This is even though it was going to result in the destruction of an entire country and create a security concern for the sub-region.

See also Obama’s speech On Authorization of Odyssey Dawn, Ltd Military Action in Libya

Similarly, the imposition of foreign religious systems and colonial education was designed to undermine African cultures and replace indigenous knowledge systems with European ideologies that would ultimately benefit European economies.

Despite these historical and contemporary examples, many Africans continue to misinterpret the actions of European powers, mistakenly believing that Western governments and institutions act out of altruism or a genuine desire for African development.

Consider the widespread support for foreign aid programs and partnerships which often come with different strings attached, or lead to the exploitation of Africa’s natural resources under the guise of investment.

The unfortunate truth is that Europeans perfectly understand this dynamic—they recognize that Africa’s vast resources and strategic location are critical to their economic dominance.

It is only the Africans who fail to fully comprehend this reality, still clinging to the hope that European powers have Africa’s best interests at heart.

This flawed calculation leaves the continent vulnerable to continued exploitation and hinders any meaningful path toward true autonomy and self-determination. What about the complexity of White Savior as created by European missionaries in Africa?

What is The Psychological Effects of Worshiping a White Savior by Africans?

The devotion to European Christianity is also tied to the widespread reverence for the figure of Jesus, who is almost universally depicted as a white, European man. This has been one of the most insidious legacies of colonial Christianity: the portrayal of a foreign god, represented in a European image, as the ultimate savior of all humankind.

On blackbraziltoday.com, you will find an interesting article “The White Savior Complex: Is White Volunteer Work in Africa?”. Consider giving it a read. The article talks about the way some people approach volunteer work in Africa and other marginalized communities, where their actions are often more about self-promotion than genuine aid.

It highlights the problematic dynamic of well-meaning but misguided individuals—often from wealthy, predominantly white backgrounds—who travel to impoverished areas, taking photos with local people, particularly children, and sharing them on social media to showcase their “generosity.”

This practice, though might be insignificant to many, is clearly intentional, and reinforces harmful stereotypes of Africa as a land of misery and helplessness, ignoring the complex, systemic causes of poverty and the contributions of local activists.

The phenomenon has been criticized for treating African people as objects of charity, rather than empowering them, and for overshadowing the efforts of grassroots organizations working for real change.

Critics argue that true support for global inequality requires not just volunteer work, but structural action, such as challenging the global economic systems that perpetuate poverty.

In other areas, you will see African Christians clearly worshiping “white Jesus” as the redeemer—the one who will liberate them from the chains of sin, poverty, and oppression. But when you pause and think about it, this imagery subtly affirms a larger, more troubling narrative: the idea that salvation, both spiritual and worldly, comes from Europe.

See also Alexander Crummell: Emigration, an Aid to the Evangelization of Africa

The Christian faith—and by extension, the King James Bible—becomes intertwined with the notion that Africa needs European wisdom, guidance, and intervention to achieve spiritual and material salvation.

This psychology is deeply ingrained. According to studies conducted by the Pew Research Center, nearly 50% of Africans identify as Christian, with countries like Nigeria, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo holding some of the largest Christian populations in the world.

Yet, as already explained earlier, despite this widespread adherence to Christianity, many African societies continue to grapple with the legacies of poverty, corruption, and political instability that were exacerbated by colonial rule.

The question then arises: why does the very faith imposed during colonialism continue to hold such dominance over African societiestoday? The answer lies in the deep-rooted identity crisis that many Africans continue to face.

This crisis keeps them trapped in a perpetual cycle of self-destructive colonial legacies, unable to break free from the cultural and spiritual frameworks that were imposed upon them.

The enduring influence of colonialism has left many Africans disconnected from their indigenous identities, leading to a continued reliance on the very systems that once sought to oppress them.

Breaking Free from the Chains of the ‘White Savior’

If we are to truly move toward decolonization—politically, economically, and intellectually—we must begin by confronting the legacy of colonial religion. Reclaiming African spirituality means acknowledging the harm that colonial religious imposition has done to African identities and how it continues to shape cultural norms today.

See also The Decolonization of Mindset among Africans – Dr. Kiatezua Lubanzadio Luyaluka

In the article “What Is White Savior Complex and Why Is It Harmful?” available on health.com, it was stated that The White savior complex refers to the belief, often unconscious, that White individuals possess superior knowledge, skills, or power to solve problems faced by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities.

Those with this mindset believe they are better positioned to address issues impacting these communities than the people directly affected.

This complex can manifest in both popular cultures, where a White character “saves” a marginalized group, and in real life, when White individuals intervene in the aftermath of crises or inequalities, often without fully understanding or addressing the root causes of the issues.

Africans must therefore be given the intellectual space to reflect on their religious history. Pan-African scholars like Chinua Achebe and Kwame Nkrumah challenged the colonial narratives that portrayed Africa as a “dark continent” in need of Western enlightenment.

See also Dr. Kwame Nkrumah And His Idea Of Pan-Africanism with Joseph Andoh Quarm

In the same vein, modern scholars and religious leaders must engage in a critical reassessment of the religious tools that were used to control African minds and suppress indigenous belief systems.

Decolonizing Christianity in Africa doesn’t necessarily mean rejecting Christianity outright. Instead, it means reexamining the faith from its colonial roots and asking difficult questions about the way it has been used to perpetuate mental and cultural domination.

It also means reasserting African identity and spirituality, embracing the continent’s rich religious diversity—whether that be in the forms of traditional African religions, Islam, or a Christianity that is truly African in expression.

Conclusion: Toward a New Spiritual Freedom

The path to true intellectual, spiritual, and cultural freedom requires the courage to question long-held beliefs, to examine the impact of history on our identities, and to assert an African-centered vision of both faith and the future.

If Africans can begin to decolonize their religious practices, they will take one significant step closer to reclaiming their full humanity. The journey to liberation, after all, is both a political and a spiritual one.

Want to learn more about storytelling? Start by downloading the first chapter of The Storytelling Mastery.