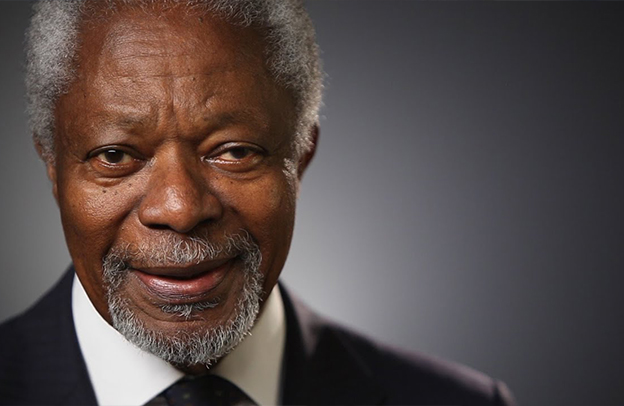

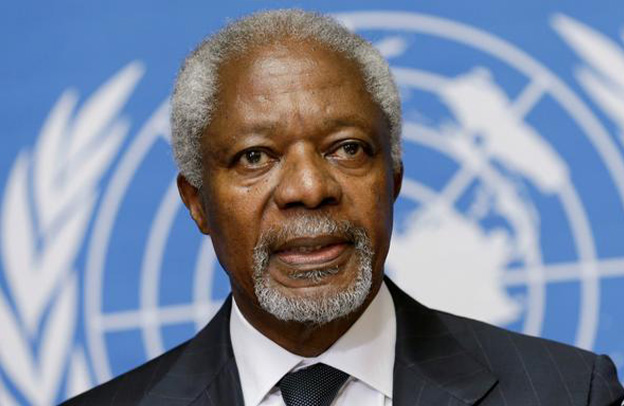

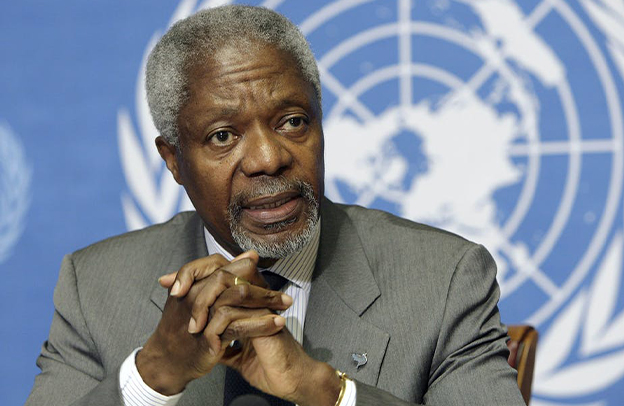

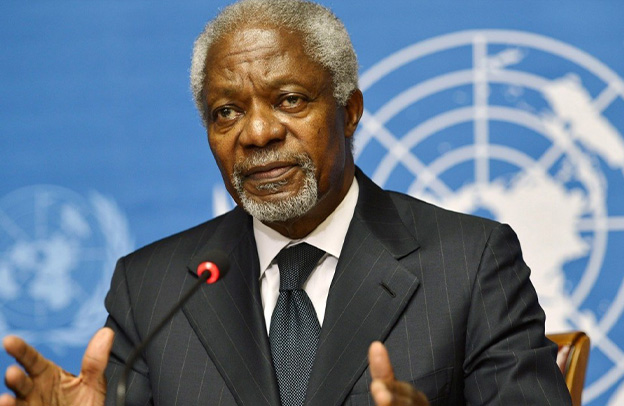

Press Conference at UN Headquarters: Kofi Annan Series

This is a transcript of the press conference by secretary-general Kofi Annan at united nations headquarters, 19 December 2006. Kofi Atta Annan was a Ghanaian diplomat who served as the seventh Secretary-General of the United Nations from January 1997 to December 2006.This is a continuation of our (Kofi Annan Series). Click here to see more from the series.

Download the first chapter of The Storytelling Series: Beginners’ Guide for Small Businesses & Content Creators by Obehi Ewanfoh.

Annan was born in April 8, 1938, Kumasi, Ghana and he died August 18, 2018, Bern, Switzerland. Kofi Annan and the UN were the co-recipients of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize.

The Secretary-General: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. I thought you would not want me to leave without getting one more chance to question me. But, I’m sure you don’t want to hear another farewell speech. I would just like, though, to acknowledge the magnificent announcement by the Spanish Prime Minister yesterday, that Spain is donating $700 million to the effort to achieve the Millennium Development Goals by 2015. This is the largest contribution yet made to the UN for this purpose by any country, and I believe it is a splendid example of international solidarity, which I hope other members will follow.

Otherwise, let me just say that I am still at work. I shall be in the office all this week, and I will still be available next week if I am needed. And, of course, I will continue until midnight 31 December.

You might also like to read – Press Conference at UN Headquarters: Kofi Annan Series

But, obviously, I am now also working very closely with my successor to help him take over smoothly on New Year’s Day. There are a number of questions or issues we’re following very closely, including Lebanon. I’m particularly anxious that there be no break in our handling of the continuing crisis in Darfur, and that is why I asked him, Mr. Ban, to come with me when I briefed the Security Council yesterday.

As you know, I spoke again to President Bashir of Sudan over the weekend, and I am now sending Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah to Khartoum to make one last effort to clarify the agreement with the Sudanese Government on the proposed UN-AU joint peacekeeping force. Mr. Ban and I have also agreed to ask Jan Eliasson to serve as Special Envoy on the Darfur crisis, and I am very glad that Jan has accepted, and I expect him to [assume] his activities [on Sudan] at the beginning of the year.

I am still hopeful that we shall be able to clarify the remaining issues with the Sudanese Government, and that, in the New Year, there will be a force on the ground to bring effective protection and security to the suffering people of Darfur, while the effort to bring all parties into a political agreement is stepped up. But, I cannot overstate the urgency of the situation, which continues to deteriorate even as we speak.

Yet more humanitarian relief workers were forced to flee the region over the weekend. More people are dying every day, and will die in much larger numbers if there is not a real improvement in security very soon. While many factors contribute to this situation, including the rebel attacks, the Government of Sudan should be in no doubt that the world will hold it primarily responsible for the fate of its citizens.

Let me now take your questions.

Question: On behalf of the United Nations Correspondents Association, allow me to first welcome you. And then, of course, this is your last press conference and mine, too, so I would wish you good luck and goodbye and hope you have a good time when you go underground; and when you surface, please do come and see us sometimes.

My question today is, given the sharpening of contradictions between the Islamic world in the backdrop of the “Alliance of Civilizations” that is going on over here, and contradictions which are now being manifested — like today, in The New York Times alone, I saw three news items which defined the crisis which is growing in the European countries.

And you have also termed, besides Darfur, there is Iraq, which has become the killing fields. There is the situation in Palestine. In your opinion, what is the crisis which will ultimately undermine the world peace the most? Can you please tell us?

The Secretary-General: I think we should be concerned about all crises, but I have indicated that one crisis that has impact well beyond its borders on people far away from the conflict is the Israeli-Palestinian issue. And I am encouraged that, recently, there has been a sense that we need to make a renewed attempt to resolve that issue. But, that would also require that one works with the Palestinians to establish unity amongst themselves, and then proceed from there.

I think, on the work of the Alliance of Civilizations, one thing that came through very clearly is that, some of the conflicts we are seeing — believing that it is religion which is at the basis, not necessarily so. Most of it is political, political policies and differences, which pushes people sometimes to take the law into their own hands and go in another direction. The issue is not the faith. Yes, in some situations the faithful behave very badly towards each other, but the basis of most of these conflicts is political.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, critics and commentators will say what they will about the Secretary-General. But, what is important, I’d like to say, is that, in your time in office, you have given hope to millions of dispossessed people, and for that, I would say, you will be well remembered. But my question: as the Secretary-General, you convey moral leadership. Now, how does a former Secretary-General continue to use, without the bully pulpit, that former status to convey and to give moral leadership to the world?

The Secretary-General: Well, there are many issues which have been of great concern to me over the past 10 years, and I’m not going to drop them because I leave office. I will follow these issues. I would want to work on some of the African issues, some of the human rights and the governance issues and the global warming issues. I will work with others and speak up from time to time when it’s necessary. I don’t think I’m going to fade away. I will continue to be active in those areas.

Question: What do you think were the three — not a whole laundry list — top achievements in your time of office, and what do you think are the three worst moments?

The Secretary-General: I would say the work we did on human rights and the approval of the responsibility to protect, by the Member States. Second, I would say that our fight for equality, our determination that any inequality between States and within States should be reduced and that, in a world where you have extreme poverty and immense wealth sitting side by side, it’s not sustainable. And we came up with the Millennium Development Goals, which today is our common framework for development.

I would also say that the work we’ve done on infectious diseases, from HIV/AIDS to the work we did with WHO on the avian flu, were important. And, of course, I’ve also made the UN a truly partnership organization, realizing, from the beginning, that we couldn’t do everything, and we had to know what we can do, what others do better, what we have to do with others. And, I think, opening up to the private sector, foundations, universities and civil society, we have been able to bring on partners and thus expand our activities.

I think the worst moment, of course, was the Iraq war, which, as an organization, we couldn’t stop. I really did everything I can to try to see if we can stop it.

The other really painful one was the loss of our colleagues in Baghdad, which was a very painful thing for all of us, and for me personally. They were not just colleagues; they were true friends. And, I think nothing had hit me as much as — was the loss of my twin sister.

I think that the third one, if I may say so, was also the “oil-for-food” [programme], and the way it was exploited to undermine the Organization. Yes, there was some mismanagement. But, I think, when historians look at the records, they will draw the conclusion that, yes, there was mismanagement; there may have been several UN staff members who were engaged, but the scandal, if any, was in the capitals and with the 2,200 companies that made a deal with Saddam behind our backs.

Of course, I hope the historians will realize that the UN is more than oil-for-food. The UN is the UN that coordinates tsunami [relief], the UN that deals with the Kashmir earthquake, the UN that is pushing for equality and fighting to implement the Millennium Development Goals, the UN that is fighting for human dignity and the rights of others, and all the other aspects. That was a very special programme, the oil-for-food, we were asked to implement. So, please don’t generalize from the particular.

Question (interpretation from French): I would like to ask you a question in French. You are leaving during the crisis in Côte d’Ivoire and Darfur. When you say that Africa has gained more stability, how far can United Nations peacekeeping operations improve this?

The Secretary-General (interpretation from French): Yes, these are ongoing conflicts, Darfur and Côte d’Ivoire. With United Nations support and with peacekeeping operations, these situations have been regulated, in Sierra Leone and Liberia too, and, more recently, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. People thought it would be impossible that the crisis in Burundi could be resolved — and in Angola, too, peace has been restored. So, there has been progress made in Africa, but there are major conflicts still that have to be resolved. We need to do everything to resolve them, to enable Africans to focus on social and economic development.

Question: First, I wonder if you could clarify one point for us on Jan Eliasson. You called him a Special Envoy. Is there going to be a new Special Representative also appointed sometime to replace Jan Pronk? If you could clarify that.

Then, my question is, since you’re leaving, you sort of get a magic wand to look at the world. You talk about the importance of the United Nations as an institution, particularly in this era of globalization. Yet, the UN has many critics. What would you do to sort of change perceptions — to try and make people around the world realize the importance of working and living together?

The Secretary-General: On the first question, let me say that Jan Eliasson would work the diplomatic channels. He will be working mainly outside Sudan, working with capitals and Governments and encouraging them to stay engaged to support our efforts and to work with us in Darfur in our search for a solution.

We will designate a new Special Representative to replace Mr. Pronk. That individual will be jointly appointed by the African Union and the United Nations, as part of this proposal that we have on the table: the three-phased proposal. We are looking at names, and we haven’t decided on anyone yet, but, if it’s not done by the end of the year, my successor will have to do it.

On the question of trust and belief in the UN, let me say that the perception and appreciation of the UN differs from continent to continent and from region to region. There are countries and regions in the world where the work and operations of the UN is highly appreciated.

I know we have vocal critics in the United States. They may be in the minority, but they are very vocal. They are not always fair in their criticism. We do accept honest and fair criticism, but I think what I should say is that those who, instead of working to strengthen the UN, would want to destroy it or weaken it, they should ask themselves: if the UN is no longer here, how do we deal with some of the issues which cross borders? Who is going to speak out and stand up for the poor, the weak and the voiceless? Whom are we going to turn to when you have the “ Lebanons”? We saw it last summer.

The UN was the only organization that could have stepped in and do what we did. Who is going to coordinate the next tsunami? Or the Kashmir earthquake? Who is going to send in the troops to protect the weak and the helpless? And who is going to feed the internally displaced in Darfur and other regions?

They just have to think sincerely and simply and look around them — but I’m not sure — that’s a problem — you can’t fight ideology.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, you came back from a very important trip that you made to the Middle East — and one of your major trips — with excellent grades that you gave to Iran, to Syria about Lebanon, and to Israel as well. But now, as you know, you never received any fulfilment of the promises made to you, including the delineation of borders. Both Iran and Syria oppose a tribunal. Were you misled? Do you think that you were set up to say, to give these good grades? And are you disappointed that you are leaving office with promises unfulfilled?

And, finally, would you clarify, for the record, once and for all — is it true that you are the one who made Detlev Mehlis take away the names of suspects from his report that included, of course, the brother and the brother-in-law of the Syrian President?

The Secretary-General: Let me start with the last one. Even though Mehlis worked for the UN and reported to the Council frequently, and I saw him, you seem to know more about it than I do, as to who was guilty and who was on the list. Quite frankly, we didn’t get into any names. Investigations were going on, and I was very anxious not to do anything to interfere with the investigations. And, of course, after Mehlis left, we brought in [Serge] Brammertz, who is going about his work methodically to build up cases that will stand up in court. He is professional, he is very calm, but he is doing very solid work and, hopefully, it will stand up when the tribunal opens its work.

Here is another article you might like – Talking About The Crisis of Democracy by Kofi Annan: Kofi Annan Series

On the first part of your question, I really do not see the purpose of your question. I did go to the Middle East. I did 13 countries in 15 days. I pressed both Iran and Syria to cooperate with the international community in the implementation of [resolution] 1701, and I think that was the right thing to do. We pressed them also to try and protect their borders — the Syrian-Lebanese borders — so that arms do not come through. But, Rome wasn’t built in a day. I did not come out and say they promised me they are going to do everything in one week and do this.

This is a process. The pressure will have to be maintained on them. The pressure will have to be maintained on both and, in fact, recently, I called both of them to tell them they need to work and use their influence with the Lebanese parties to ensure that there is national unity, they resolve their differences through dialogue and that they should be patient. I hope my successor would also keep the lines open, to be able to call them and steer them in the right direction. But, these things do not happen overnight. The pressure has to be maintained.

When we agreed with Syria, after the resolution, that they should withdraw their troops and the security forces, they gave their commitment, and we worked with them. And the pressure was maintained, and they are gone. And so, we have to keep maintaining the pressure and, also, be a little bit patient. It can’t happen in a week.

Question: Hi. Mr. Secretary-General, in Canada, there is a national debate now over whether our country should continue to take part in the war in Afghanistan — the UN-sanctioned war in Afghanistan. So far this year, nearly 40 Canadian soldiers have died in that conflict. Part of the debate is whether we should hunt down and track insurgents and try to stop them, or whether we should focus more on reconstruction efforts.

I am curious: from your vantage point, what do you think Canada and the other coalition countries need to do in Afghanistan?

The Secretary-General: Let me first offer my deepest condolences and sympathy to the families and the loved ones of the 40 soldiers you’ve referred to. It’s always extremely painful when a peacekeeper dies in the line of duty.

I think the question you posed is an important one, and it’s not only relevant to Afghanistan. It’s relevant in other theatres. Reconstruction can only take place where there is a reasonably secure environment. Where there is serious fighting, it is extremely difficult to proceed with reconstruction.

I’m sure there are some parts of the country where reconstruction can go forward, but I think it is important that the Government of Afghanistan and the international community that is there to help them focus on anything they can do to provide a relatively stable environment for that kind of reconstruction to go on.

At the same time, efforts should also be made to get the people involved to really focus on the positive things: to win, to get a political and social settlement, and work at the grassroots and community level; one cannot do this with military action alone, and I know there are discussions going on along these lines.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, last summer, on this trip to the Middle East, you announced the facilitator to deal with the Israeli kidnapped soldiers. Where is it now? Can you update us? And, also, can you tell us how was it that the lease on your apartment transferred to your brother Kobina?

The Secretary-General: On your first question, let me say that the facilitator is working very hard at this. He is working with both parties and has been going there almost on a weekly basis. Recently, he’s had to delay one or two trips because of what’s happening in Lebanon. And I hope that he will be successful in getting the two soldiers released. Both parties are engaged, and I hope it will move faster, and sooner rather than later. But, we are doing everything that we can.

On your second question, I know that my Spokesman answered on the thing, but I do not hold a lease on an apartment or own an apartment on the island. I think you know that my brother lived there, so I don’t think I can say any more about that.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, I would like your comments, Sir, concerning the refusal by both Israel, through their Prime Minister in the Blair conference, and the United States, to open negotiation with Syria, despite the offer by the Syrian President to open negotiation with Israel and to conduct a dialogue with the United States, although you’ve called for this more than once.

Secondly, in Sudan, some officials are saying that they would like immunity from prosecution to facilitate the entrance of the United Nations forces. Do you think that’s a feasible prospect?

The Secretary-General: On your first question, I know that Prime Minister Blair has been very interested in the Middle East issue, and he is in the region at the moment, and he had indicated that it would be constructive to talk to Syria. I share that view, and I hope that will happen.

I know that Syria has indicated that it is ready to negotiate, but it takes two to do that. And I hope that, with the renewed interest in what is going on in the region, that we would eventually come up with a process that will work on all three tracks: Israeli-Palestinian, Syrian and the Lebanese one. In my report to the Council, I did put forward some proposals.

On your second question, the UN troops are not going to Darfur to arrest Sudanese leaders. Their responsibility and mandate will be to help create a secure environment in Darfur that will allow us to protect the internally displaced, allow access to the needy by the humanitarian workers, as well as give us time to speed up the political process and strengthen the ceasefire and ensure that we have an effective ceasefire commission that monitors it. But we are not going there to arrest; that is not our mandate. And so, I don’t think one should keep the troops out because they think we are coming there to arrest them.

Question: You’ve listed the best and the worst. What was your deepest personal regret? And there seems to be a buzz in the building about more manager-CEO than diplomat rock-star. Maybe that’s directed at you. Is that the best way to go forward for this new administration?

The Secretary-General: Well, I have said that the new administration, that my [successor], has to do it his way. I do not know how he is going to do it. I did it my way, and I hope he will do it his way — and do what he is comfortable with and really try to protect the ideals and the principles of the Charter. But, I do not think I can tell him how to proceed.

Question: And your personal regret?

The Secretary-General: I think that I answered it when I answered…

Question: That was something that happened. What about something that maybe you feel that you could have done differently, either personally or involved in professional activities — oil-for-food, Baghdad decisions?

The Secretary-General: I think I’ll pass on that one.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, now that Israel has come out of the nuclear closet, how do you think that might affect the atmosphere in the region, and how can the Middle East peace process move forward with that new element in the atmosphere?

The Secretary-General: I hope that new element will not have a negative impact on the peace process, if it genuinely gets off the ground. But the Middle Eastern nations have often talked about a nuclear-free zone. But, with the developments in the region at the moment, I have a feeling that desire — that dream — may not be achieved; it will elude them because of the developments in Iran and the Israeli situation.

You have noted several Governments in the region say they are going to explore nuclear facilities for energy. So, what I am worried about is we may see competitive development of these devices, and we need to take real efforts to ensure that we don’t get into that situation in the region. And, therefore, the work of the [International] Atomic [Energy] Agency and the Security Council is extremely important in the non-proliferation area.

Question: The recent experiences you’ve had talking with President Bashir about Darfur have been: you’ve come away thinking you have an understanding, and then he will — or one of his officials makes a wild speech in Khartoum saying the numbers are made up; it’s all a Jewish conspiracy to build up humanitarian groups; and that the United Nations will never be welcomed there. From your conversations in recent days that led you to send Ahmedou [Ould-]Abdallah out there, do you have an understanding now that you think you really can deal with him and that he will keep his part of the bargain?

The Secretary-General: The proof of the pudding will be in the eating. But several other leaders have been to see him. In fact, the US envoy, Andrew Natsios, was there a few days ago. When I spoke to him, he indicated that the Abuja Agreement has been endorsed by his Council of Ministers and that he was waiting for Security Council endorsement to move forward. We are going to test that. Ould-Abdallah is going with very specific questions and clarifications, which will allow us to move forward expeditiously.

I have also made it clear to him and to the African Union that the possibility that the United Nations will pay for the operations will only happen if the Council has confidence that the arrangements that are being put in place will make a difference and there will be a credible force on the ground to do what is required. So, when Ahmedou comes back, we will have a sense of whether he’s got the commitments or not. Yesterday, we discussed it intensively with the Security Council members, and Mr. Ban was also with me. So, we are awaiting Ahmedou’s return. But, for the moment, he said: “As soon as the Council adopts it, I will give instructions.” We shall see. But we are pressing.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, first of all, I’d like to thank you, for the past 10 years, for all your answers on the Balkans, some of which you helped me to make even headlines. I would like to ask you this last time, Sir, something else though. It is not on Bosnia; it is not on Balkans. Bearing in mind yesterday’s very productive meeting on the Alliance of Civilizations, do you think that we reached a point of understanding — or did we reach the point that, even if it was theoretically in the air, the clash of civilizations is now avoided?

The Secretary-General: I don’t think that an effort like the Alliance of Civilizations can be expected to solve all problems. But, at least it is a major effort to try and develop understanding and dialogue amongst peoples.

And I also indicated — the work of the High-level Group also makes clear that we talk of clash of civilizations, dialogue among civilizations, Alliance of Civilizations, but that, indeed, in today’s globalized world, we are living in one civilization. Sometimes we are brutal to each other. But, when you think about it very carefully, we all have different identities: we may be a Ghanaian, you may be a Christian, you may be a Muslim. There are all sorts of things. And this we see in many parts of the world. But, when you look at the direction the world is going, we should emphasize what unites us much more than what divides us.

But I think the effort of the Alliance of Civilizations, which is going to continue, they would want to set up a practical mechanism to implement the recommendations that came out — I hope will help encourage dialogue and understanding around the world. I think that’s the only thing that it can do, not more than that.

Question: I wanted to say that Africa is one of the places where the UN has a very high credibility; so does the Secretary-General, which is why I ask this question. Some politicians in Nigeria have said that the UN should play a role in the election that is coming up next year, which is a major election in Africa. Do you think that the UN should have a role to play in the elections? And then, are you satisfied with the pre-election preparations for that presidential and general elections?

The Secretary-General: Let me say that I’m not close enough to comment on the pre-election preparations. But what I can say is that the UN will be in a position to help if we were to be asked by the Government. We have helped in well over 100 elections. And, as you know, we organized a very important one in the Democratic Republic of [the] Congo recently.

But the request has to come from the Government, and if we are going to participate, the request has to come fairly early, so that we will be able to work with them on the technical aspects of the elections to be able to assure ourselves that it will proceed smoothly, at least from the technical point of view. And, in some situations, we have coordinated the work of international observers. But that must be based on a request from the Government.

Question: Out of 44 years of international public service, you have dealt with hundreds of world leaders. Who was the most impressive leader you dealt with, and who disappointed most?

The Secretary-General: They all have their talents.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, just noting what you said about Iraq, or the breaking out of the Iraq war being one of the points of your disappointment; what could the Security Council do in future cases, particularly now that people are concerned about Iran’s case? My second quick question, Sir: Do you leave your post feeling satisfied you have done your best concerning the Palestinian-Israeli conflict?

The Secretary-General: I think the Council will have to continue doing its work. You mentioned Iran, which implies that there is concern that there may be another military operation there. First of all, I don’t think we are there yet, or we should go in that direction. I think it would be rather unwise and disastrous. I believe that the Council, which is discussing the issue, will proceed cautiously and try and do whatever it can to get a negotiated settlement for the sake of the region and for the sake of the world.

I would also say that it’s not just the Security Council that should learn from the Iraq experience. Governments and peoples around the world should also learn from that experience and draw the right conclusions for future actions.

On the Palestinian-Israeli [issue], we did as much as we can. I am rather sad that, as I leave, we haven’t made much progress. I worked with the Quartet, and I think I pushed as much as I can. And I hope that the proposal I made in my last report will help move the process there forward, because I do indicate some specific measures for the Quartet and for the international community.

Question: You say that corruption here has not been as widespread as reported. Do you fear, or feel, that the Security Council has been corrupted by economic incentives, and that Saddam Hussein was able to have the oil-for-food and billions in contracts, that Iran is able to influence Russia and China through its billions of dollars in contracts? Even in the Sudan — does this pose a threat that the Security Council has been crippled and can’t take the action to live up to its name?

The Secretary-General: You are getting into [a] dangerous area. I don’t have enough evidence to say that Security Council members are guilty of corruption. I think, before we throw that word “corruption” around as easily as we do, we should look around us — look at our own countries, look at other institutions that we deal with. The Council members have a tough job, and they try to do the best they can. They are not always able to control everything. But I’m not sure that their decisions are guided only by commercial and financial interests.

Question: DearMr. Kofi Annan, first, on behalf of the Islamic Republic News Agency, I deeply want to thank you for your 10-year service and accomplishment. Good luck for your future journey.

I have one long question…

The Secretary-General: Should I take notes?

Question: As you know, Israel has officially ended its nuclear ambiguity policy, as Mr. Olmert has publicly confirmed possession of a nuclear weapon. Isn’t it double-standard behaviour between Iran having peaceful nuclear energy and Israel having a nuclear weapon?

The Secretary-General: Well, this is an issue which we’ve been discussing for a long time. You would recall that, in my recent speech at Princeton, I made clear the point that the nuclear Powers have to set an example, and that disarmament and non-proliferation go together. And, as long as nuclear Powers hold on to their nuclear weapons, and in some cases try to upgrade it — sort of vertical proliferation — claiming they need it for their defence, it is extremely difficult to tell others. They are going to claim that they need a weapon of that kind for their defence also.

But, I think Iran signed the NPT and is obliged to live by — accept the obligations of the Treaty and the decisions of the IAEA Board and, of course, the decisions of the Council. Israel, India and Pakistan are not in that situation and, therefore, have not been subjected to the kind of pressure on Iran to meet its obligations.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, my question is on Cyprus, of course.

The Secretary-General: I am surprised!

Question: You tried hard, really hard, but, unfortunately, you didn’t succeed in solving the problem. I wanted to know what is going to happen to your plan. Are you going to pass it to your successor, or the plan is dead?

The Secretary-General: We are still engaged with the parties. And, in fact, my representative on the ground, Michael Møller, is working with them to build confidence. We have certain specific activities that the two of them are engaged in. And I have indicated that, at the appropriate time, when we believe the time is right, we will name a full-time negotiator-mediator to work with them. That responsibility will fall on my successor, and I am sure he will proceed along the same lines.

I think it is important that we find a way of resolving the Cyprus issue. It is not an issue that affects only the two communities, or Turkey and [ Greece]; it has today also become a European problem, and it is something that we need to resolve as quickly as we can. And I hope the UN will press ahead to deal with it.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, I’m going to use the word “transparency” rather than “corruption”. UN reform has been a theme in recent years. But some are saying that it has been focused mostly on the Secretariat, not on the funds, programmes and agencies of the UN system. Recently, an investigative series about UNDP: your Deputy Secretary-General had only harsh words for it.

But the Spanish [Prime Minister] yesterday, sitting where you are, joined a call for transparency or providing audits of UNDP to all the Member States, rather than, as is the case now, only summaries to some Member States. I am wondering what you see as the next steps, in terms of increased transparency in the whole UN system, not only the Secretariat, and what you see as the next steps in UN reform more generally.

The Secretary-General: Well, obviously, I don’t know what my successor will have in mind. But the UN and its agencies have tried to be transparent and responsible for the resources entrusted to them, and they do provide records to their governing board and to the countries supporting them.

Quite a few of these institutions have already gone through their own reform, from UNDP to UNICEF to UNHCR, and the other agencies — ILO, UNESCO — have gone through their own institutions and report to their own governing board. And I hope they will remain vigilant and continue to do so. I don’t have the details of the issue you are referring to, but UNDP is a very responsible and serious organization and highly respected.

Obviously, I cannot say that there may not be one or two bad apples, as we have here and we have in any other institutions. But again, we have to be careful not to generalize and tar every staff member with the same brush. I have often said that the UN staff and people in these agencies deserve our appreciation and thanks.

They often serve in places where Governments are afraid to send their troops, and they really do a lot for the world. So we should also look at some of the contributions they make, not always trying to look for something to hit them on the head with. If there’s something that is wrong, you should criticize, but you should also look at the positive work that they do.

Question: Hello, Sir. I want to ask about the African Union, because, during your tenure, you’ve seen the UN work closer and closer with the African Union. How would you characterize the relationship? What problems do you think the two organizations have in understanding each other, and what needs to be done in the next six months to a year to improve the sometimes fractured relationship?

The Secretary-General: We’ve been working better and better together; we recently signed an agreement of cooperation. But, over and above the agreement, it is what happens on the ground and in our daily relationships which is very important. I am personally on the phone with the Chairman quite a lot.

But, let me say that the African Union project is an extremely difficult one. The European Union started with six member States, and the African Union started with 53, from an objectively lower economic and social base. So it is a really huge challenge. They are making progress; they don’t have the resources or the logistics.

This is part of the problem in Darfur, where they tried to do a valiant job within these limitations, and we have to do — but I think the UN and other institutions like the European Union should try and work with the African Union to strengthen the institution and improve their capacity. But I have to admit it’s a real challenge starting afresh with 53 countries in the desperate economic situation that exists on the continent and build an African Union, a united and homogeneous organization, out of it. We will continue to work with them; we will continue to stress — in fact, even as we speak, we have a peacekeeping unit there working with them on the African Union and in other areas, and we will continue.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, you have repeatedly used transparency and accountability as your watchwords in elements of United Nations reform. And I wanted to ask you, in the spirit of fair criticism, whether you are satisfied with OIOS and the job that they’ve done in terms of effectively rooting out the isolated and legitimate instances of corruption or fraud inside the UN. And, related to that, as you have surely heard, your successor, Mr. Ban Ki-moon, has continually talked about his mission to restore trust in the Organization, both between the staff and the Organization and between Member States and the Secretariat, and I wonder if you perceive that as criticism.

The Secretary-General: I think, as to the second question, you should ask him. It was his statement.

But, turning to the first one, I think OIOS is doing as best as it can. There were times when they were short-staffed. We have a new head, Inga-Britt Ahlenius, working with a small team. We have recruited additional staff and, I hope, with their strengthened capacity, they will be able to do much more than it had been possible in the past. But, I will say that, under her leadership, they are doing the best they can, and I am sure they will make a difference.

Question (interpretation from French): Good morning, Mr. Secretary-General. Before Human Rights Watch, you said, regarding Darfur, is that this crisis would show that the international community had not learned much since Rwanda and Bosnia, which seems to be a harsh judgement. Could you explain that to us? And do you think that the United Nations has not learned much since then and, if that is the case, should that not be on the list of your chief regrets?

The Secretary-General (interpretation from French): When I spoke about Darfur at that conference, the question was, if we had reacted earlier, could we have saved the situation, but we didn’t. Rather, we encouraged the African Union to establish its troops, knowing that they did not have the necessary capacity to do so.

So, yesterday, I had a very interesting talk in the Security Council. One member said that we must be careful and not use African Union troops as an alibi for inaction by the international community, and he was quite right. If we had reacted a little earlier, I do think we could have done it.

Let us not forget that the United Nations already has a force of 10,000 in Southern Sudan. I think that, if we had reacted sooner, the situation would have been even more complicated. But we also need to ensure that we do not try to lay the blame on a single person for what is going on. Obviously, I have regrets.

I regret that we were not able to resolve this as soon as possible. But there is a tendency in certain places to blame the Secretary-General for everything, for Rwanda, for Srebrenica, for Darfur; but should we not also blame the Secretary-General for Iraq, Afghanistan, Lebanon, the tsunami, earthquakes? Perhaps the Secretary-General should be blamed for all of those things. We can have fun with that, if you want.

Question: One of the most important changes in international law under your tenure was the responsibility to protect. Last time, at a press conference, in fact, you said things had changed when asked about humanitarian intervention. We wondered if you had abandoned the idea of humanitarian intervention. But specifically, the responsibility to protect is the idea that Governments lose sovereign rights if they show no willingness or capacity to protect their civilians from atrocities.

Are we at a stage now where the Sudanese Government, after three years of atrocities and not accepting any help, sufficient help, has lost sovereign rights over its own country and that we might be entering a stage where the outside world does need to intervene militarily?

The Secretary-General: Thank you, Mark, for that question. Let me say that that new principle, which is an extremely important one, will make a difference, I believe, in our world. But, we should not expect it to be fulfilled or implemented immediately or in the first year. I think, over time, you will see what difference this is going to make to international law.

But, to your specific question, let me say that Sudan has come under tremendous pressure from the international community to cooperate with that community to send in troops to help. Have we done all that we could to pressure the Government of Sudan to do what it has to do?

There are measures short of force that could be used. We have used them in other situations. Political pressure, economic sanctions and isolation — and of course, in the last resort, there is the use of force. Have we brought to bear on this situation all the capacity we have to pressure the Government to bend? And this is something that we also discussed yesterday with the Council and, hopefully, we will see some changes. In fact, yesterday, in the Council discussions, one of them said: “The P-5, you have special privileges and special responsibilities. Let us feel your weight.”

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, during your time here as the Secretary-General, you’ve made some great appointments. You had Shashi Tharoor as the head of DPI, and he created a campaign: “10 things that the media should remember”. You had Jan Egeland as the head of OCHA: “10 humanitarian crises that were forgotten”. But something that the Secretariat seems to have forgotten is the stalemate in Western Sahara. I was wondering, what sort of guidance would you give the next Secretary-General to not forget crises such as that?

The Secretary-General: I don’t think we have forgotten Western Sahara; it’s been a difficult problem to crack. In fact, Mr. James Baker, who helped me on this, told me when he decided to end his involvement, “Mr. Secretary-General, you asked me to give you a year; I’ve given you almost six to seven years.

I’ve tried everything I know of and I have not been able to resolve this issue. And I’m giving the file back to you.” We need the cooperation of the two parties. We have my Special Envoy [Peter] van Walsum, who is working actively with the two parties. And I think in all these situations, without that cooperation, it’s extremely difficult to resolve it.

The UN stands by the right of the POLISARIO, the Saharawi, for the right of self-determination. Of course, Morocco insists on autonomy. This is where the stalemate is, and we are still trying to work it. In fact, at one point, Mr. Baker gave five options to the Security Council and said: “Select one, and work with it, and push the parties to accept.” That never happened. So we haven’t forgotten it, but we haven’t found a solution.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, last week, you gave a farewell speech at the Truman Library, in which you discussed US foreign policy and the US role at the UN. If you were to give those speeches to the other P-5 members — particularly if you were to give those speeches in China and Russia — what would the message be regarding their use of the United Nations and their role in the world today?

The Secretary-General: I think the message would be basically the same. That message I gave was a message for engagement, a message for multilateralism, a message for leadership. And the P-5 have a special responsibility, and they should assume it fully. And we have also seen — those of us who live in this building — that, when they are united and there is leadership from them, the Council works very effectively.

There are 10 other members of the Council who can make things happen. The veto is a negative power: a negative power in the sense that you can use it to block, but you cannot use it to make things happen. And so they have to be careful how that veto is used; and, each time they are going to use the veto to block something, they have to ask themselves: “Is this in the collective interest?”

I don’t think it should be done purely for national interest and national benefit. They are there to act on behalf of all the 192 Member States — if you wish, it is the executive board of the Organization, and they should really bear the interests of everyone in mind.

Question: Mr. Secretary-General, one of the themes — I guess, the underlying theme of your worst moments in your answer to Evelyn’s question — is the Iraq war. What, in your final press conference, is the lesson to be learned from that war, whether the arrogance of power, or not getting the Security Council’s blessing? And, given that the Bush Administration is currently considering its next step, would you say that the war is now lost and there’s really — the only thing to do is to pull out the US troops so that no more coalition forces die and to minimize the continuing loss of civilians in Iraq?

The Secretary-General: I think Iraq has lessons for everybody: for those who were involved in the war and those who sat it out; for those who supported it and the Council that did not give approval. But let me say that, regardless of where one stood in that debate, it is important that we find a way of stabilizing Iraq. There are lots of ideas out there as to how this can be done. You have the Baker report; I understand the President is looking at other reports and has indicated that he will give a speech portraying his own views and position some time in January.

Before I came here, I met with the Iraqi Vice-President, and we discussed the situation in Iraq. And you may know that I have proposed that an international conference be set up to help the Iraqis, because I genuinely believe that, given the bitterness and the fighting that has gone on, they cannot do it on their own.

Third-party help is required. And that’s why I suggested a grouping of Iraq, its neighbours and the permanent five and the Security Council, to try and help them sort out their differences. They need to settle the political issues: the issue of reconciliation, revenue sharing, oil and taxation revenue sharing.

It’s extremely important. And I hope that, when, next time, one is dealing with a broader threat to the international community, one will wait and seek the approval of the Security Council. As I have said, a country has the right to defend itself; but, when it’s an issue of broader threat to the international community, it’s only the Security Council that has that legitimacy to authorize action on that basis.

Question: Thank you, Mr. Secretary-General, for what you have done for Lebanon during your tenure; we will be missing you. You said that Lebanon will be in the issues, and you will work on Lebanon until the end of December. Will you press President Assad to start diplomatic relations with Lebanon during that period? And also, resolution 1559 (2004) put into question the validity of the presidency of President [Emile] Lahoud, and President Lahoud called the international tribunal is unconstitutional. What is your view on that?

The Secretary-General: On your first question, I agree with you that there must be normal relations between Lebanon and Syria, and we have been pressing for establishment of normal relations — opening of diplomatic embassies in each other’s capitals — and we will continue to press, as part of the programme of action that we have. Both Governments maintain that they are prepared to establish such a relationship, and we need to press them to do it.

Check out also this article – The New World Disorder Challenges for the UN in the 21st Century: Kofi Annan Series

On the question of 1559 and the position of the President: as we all know, there’s a disagreement between the Government — Prime Minister [Fouad] Siniora and the Government on one side, and President Lahoud on the other side, who has questioned the statutes and the basis for establishing the tribunal, indicating that, as a President, he had a say and should have been consulted. And this is something that they will have to work out.

The UN cannot impose this on the Lebanese; it’s an issue that the Lebanese will have to work out. But, as far as the UN is concerned, we do have the mandate to do the investigations, and that is going on. And, as I said, Brammertz, I hope, at the end, will produce sufficient evidence for the conviction of those who may be deemed involved.

The tribunal: we are in the preparation of setting it up; we’ve done all the work. But, of course, certain decisions would also have to be taken by the Lebanese authorities for us to go forward, and I would hope that they will soon be able to resolve the impasse and the political paralysis that we see in Lebanon, to be able to move forward.

We must also remember that the cabinet unanimously voted for the establishment of the tribunal, and I hope all those who voted for it will stand by their word and not change position at this stage.

Download the first chapter of The Storytelling Series: Beginners’ Guide for Small Businesses & Content Creators by Obehi Ewanfoh.