Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative Town Hall Malaysia

At the Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative Town Hall in Malaysia, President Obama emphasized the importance of youth in shaping the future of their countries and the region. He highlighted America’s strategic focus on the Asia Pacific and outlined key priorities for collaboration, including security, prosperity, environmental sustainability, and promoting democracy and human rights. He encouraged young leaders to focus on making a positive impact in their communities and embracing diversity as a strength.

Want to learn more about storytelling? Start by downloading the first chapter of The Storytelling Mastery.

Moderator Anita Woo: Welcome to the Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative Town Hall. My name is Anita Woo, your moderator this afternoon. Today we have the crème de la crème of ASEAN youth right here, gathered in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in University of Malaya’s Tunku Chancellor Hall.

Having produced two Malaysia prime ministers, this venue is no stranger to young leaders, such as yourselves. We are here because, as youth under the age of 35, we currently represent 60 percent of the ASEAN population; and being the single largest demographic in ASEAN, we not only have an impact on our respective nations, but also across the region.

From a global perspective, although ASEAN covers just three percent of land area, ASEAN is a single — as a single identity would rank as the seventh largest economy in the world; however, each nation within ASEAN is in a different place in our journeys towards development, each journey unique.

Deep poverty persists in the region, but one of the leaders tackling this issue is Indonesia’s Dr. Sri Mulyani Indrawati, who is currently managing director of World Bank Group.

Similarly, although the record on upholding human rights and democratic governance within the region still leaves much to be desired, Aung San Suu Kyi heroic struggle and triumph proves that mountains can be moved with determination and tenacity.

ASEAN young entrepreneurs don’t have to look far to know that success is within their reach as AirAsia’s Tan Sri Tony Fernandes carved his success from within this very region, Moreover, with a thriving scene in Southeast Asia — creative scene — who knows? The next Jimmy Choo could be amongst us this very moment.

As our region faces the challenges inherent in a rapidly developing nation and economy, where perspectives on education, business, environment must change with the times, we should use our ingenuity and entrepreneurial spirit to change how we plan to overcome these obstacles and emerge stronger than ever. Southeast Asia is one of the diversity-rich regions, home to an array of cultures and histories, and as we know, it was once even home to President Obama. The future of ASEAN will lie in its ability to not only celebrate this diversity, but to harness it as a key building block for our success.

Today the President himself will be taking questions directly from those present here, as well as questions submitted to you — submitted by you through Facebook and Twitter from around the region.

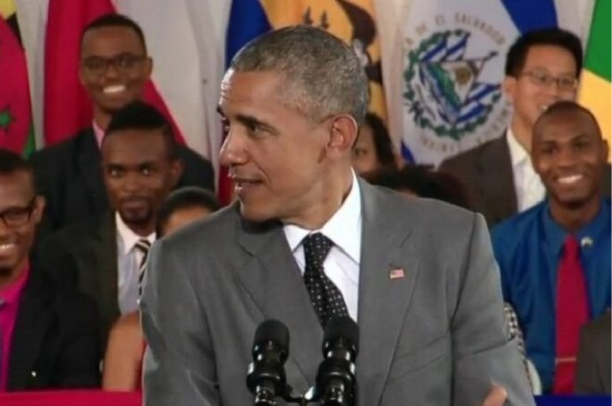

Without further ado, please join me in welcoming to stage the 44th President of the United States, President Barack Obama!

President Obama: Hello, everybody. Well, good afternoon. Selamat petang. Please, everybody have a seat. It is wonderful to be here and it is wonderful to see all these outstanding young people here.

I want to thank, first of all, the University of Malaya for hosting us. I want to thank the Malaysian people for making us feel so welcome. Anita, thank you for helping to moderate.

These trips are usually all business for me, but every once in a while I want to have some fun, so I try to hold an event like this where I get to hear directly from young people like you — because I firmly believe that you will shape the future of your countries and the future of this region. And I’m glad to see so many students who are here today, including young people from across Southeast Asia. And I know some of you are joining us online and through social media, and you’ll be able to ask me questions, too.

This is my fifth trip to Asia as President, and I plan to be back again later this year — not just because I like the sights and the food, although I do, but because a few years ago I made a deliberate and strategic decision as President of the United States that America will play a larger, more comprehensive role in this region’s future.

I know some still ask what this strategy is all about. So before I answer your questions, I just want to answer that one question — why Asia is so important to America, and why Southeast Asia has been a particular focus, and finally, why I believe that young people like you have to be the ones who lead us forward.

Many of you know this part of the world has special meaning for me. I was born in Hawaii, right in the middle of the Pacific. I lived in Indonesia as a boy. Hey! There’s the Indonesian contingent. Yes, that’s where they’re from. My sister, Maya, was born in Jakarta. She’s married to a man whose parents were born here — my brother-in-law’s father in Sandakan, and his mom in Kudat. And my mother spent years working in the villages of Southeast Asia, helping women buy sewing machines or gain an education so that they could better earn a living.

And as I mentioned last night to His Majesty the King, and the Prime Minister, I’m very grateful for the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia for hosting an exhibit that showcased some of my mother’s batik collection, because it meant a lot to her and it’s part of the connection that I felt and I continue to feel to this region.

So the Asia Pacific, with its rich cultures and beautiful traditions and vibrant society — that’s all part of who I am. It helped shape how I see the world. And it’s also helped to shape my approach as President.

And while our government, our financial centers, many of our traditions began along the Atlantic Coast, America has always been a Pacific nation, as well. Our biggest, most populous state is on the Pacific Coast. And for generations, waves of immigrants from all over Asia — from different countries and races and religions — have come to America and contributed to our success.

From our earliest years, when our first President, George Washington, sent a trade mission to China, through last year, when the aircraft carrier that bears his name, the George Washington, helped with typhoon relief in the Philippines, America has always had a history with Asia. And we’ve got a future with Asia. This is the world’s fastest-growing region. Over the next five years, nearly half of all economic growth outside the United States is projected to come from right here in Asia.

That means this region is vital to creating jobs and opportunity not only for yourselves but also for the American people. And any serious leader in America recognizes that fact. And because you’re home to more than half of humanity, Asia will largely define the contours of the century ahead — whether it’s going to be marked by conflict or cooperation; by human suffering or human progress. This is why America has refocused our attention on the vast potential of the Asia Pacific region.

My country has come through a decade in which we fought two wars and an economic crisis that hurt us badly — along with countries all over the globe. But we’ve now ended the war in Iraq; our war in Afghanistan will end this year. Our businesses are steadily creating new jobs. And we’ve begun addressing the challenges that have weighed down our economy for too long — reforming our health care and financial systems, raising standards in our schools, building a clean energy economy, cutting our fiscal deficits by more than half since I took office.

Though we’ve been busy at home, the crisis still confronts us in other parts of the world from the Middle East to Ukraine. But I want to be very clear. Let me be clear about this, because some people have wondered whether because of what happens in Ukraine or what happens in the Middle East, whether this will sideline our strategy — it has not. We are focused and we’re going to follow through on our interest in promoting a strong U.S.-Asia relationship.

America has responsibilities all around the world, and we’re glad to embrace those responsibilities. And, yes, sometimes we have a political system of our own and it can be easy to lose sight of the long view. But we have been moving forward on our rebalance to this part of the world by opening ties of commerce and negotiating our most ambitious trade agreement; by increasing our defense and educational exchange cooperation, and modernizing our alliances; by participating fully in regional institutions like the East Asia Summit; building deeper partnerships with emerging powers like Indonesia and Vietnam.

And increasingly, we’re building these partnerships throughout Southeast Asia. Since President Johnson’s visit here to Malaysia in 1966, there’s perhaps no region on Earth that has changed so dramatically. Old dictatorships have crumbled. New voices have emerged. Controlled economies have given way to free markets. What used to be small villages, kampungs, are now gleaming skyscrapers. The 10 nations that make up ASEAN are home to nearly one in 10 of the world’s citizens. And when you put those countries together, you’re the seventh largest economy in the world, the fourth largest market for American exports, the number-one destination for American investment in Asia.

And I’m proud to be the first American President to meet regularly with all 10 ASEAN leaders, and I intend to do it every year that I remain President. By the way, I want to congratulate Malaysia on its turn to assume the chairmanship of ASEAN next year. Malaysia plays a central role in this region that will only keep growing over time, with an ability to promote economic growth and opportunity, and be an anchor of stability and maritime security.

Now, one of the things that makes this region so interesting is its diversity. That diversity creates a unique intersection of humanity — people from so many ethnic groups and backgrounds and religious and political beliefs. It gives Malaysia, as one primary example, the chance to prove — as America constantly tries to prove — that nations are stronger and more successful when they work to uphold the civil rights and political rights and human rights of all their citizens.

That’s why, over the past few years, Prime Minister Najib and I have worked to broaden and deepen the relationship between our two countries in the same spirit of berkerja sama that I think so many of you embody. The United States remains the number-one investor in Malaysia. We’re partnering to promote security in shipping lanes. We’re making progress on the Trans-Pacific Partnership to boost trade that supports good jobs and prosperity in both our countries. Today, I’m very pleased that we’ve forged a comprehensive partnership that lays the foundation for even closer cooperation for years to come.

But our strategy is more than just security alliances or trade agreements. It’s also about building genuine relationships between the peoples of Asia and the peoples of the United States, especially young people. We want you to be getting to know the young people of the United States and partnering well into the future in science and technology, and entrepreneurship, and education.

One program that we’re proud of here in Malaysia is the Fulbright English Teaching Assistant Program. Hey, there we go. Over the past two years, nearly 200 Americans have come here, and they haven’t just taught English — they’ve made lifelong friendships with their students and their communities.

One of these Americans, I’m told, was a young woman named Kelsey, from a city in Boston — the city of Boston. Last year, after the Boston Marathon was attacked, she taught her students all about her hometown — its history and its culture. She taught them a phrase that’s popular in Boston — “wicked awesome.” So that was part of the English curriculum.

And so her students began to feel like a place — that this place, Boston, that was a world away was actually something they understood and they connected to and they cared about. They responded by writing get-well cards and sending them to hospitals where many of the victims were being treated.

Partnerships like those remind us that the relationship between nations is not just defined by governments, but is defined by people — especially the young people who will determine the future long after those of us who are currently in positions of power leave the stage. And that’s especially true in Southeast Asia, because almost two-thirds of the population in this region is under 35 years old. This is a young part of the world.

And I’ve seen the hope and the energy and the optimism of your generation wherever I travel, from Rangoon to Jakarta to here in KL. I’ve seen the desire for conflict resolution through diplomacy and not war. I’ve seen the desire for prosperity through entrepreneurship, not corruption or cronyism. I’ve seen a longing for harmony not by holding down one segment of society but by upholding the rights of every human being, regardless of what they look like or who they love or how they pray. And so you give me hope.

Robert Kennedy once said, “It is a revolutionary world that we live in, and thus it is young people who must take the lead.” And I believe it is precisely because you come of age in such world with fewer walls, with instant information — you have the world at your fingertips, and you can change it for the better. And I believe that together we can do things that your parents, your grandparents, your great-grandparents would have never imagined.

But today I am proud that we’re launching a new Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative to increase and enhance America’s engagement with young people across the region. You’re part of this new effort. You’re the next generation of leaders — in government, in civil society, in business and the arts.

Some of you have already founded non-profit organizations to promote human rights, or prevent human trafficking, or encourage religious tolerance and interfaith dialogue. Some of you have started projects to educate young people on the environment, and engage them to protect our air and our water, and to prevent climate change. Some of you have been building your own ASEAN-wide network of young leaders to meet challenges like youth unemployment. And I know that some of you have been spending this weekend collaborating on solutions to these major issues.

And over the next few months, across Southeast Asia, we’re going to find ways to listen to young people about your ideas and the partnerships we can then build together to empower your efforts, develop new exchanges, connect young leaders across Southeast Asia with young Americans.

So that’s part of what we’re starting here today. And before I take your questions, let me just close by sharing with you the future that I want to work for in this region, about where we want America’s rebalance in the Asia Pacific to lead, about the work we can do together.

I believe that together we can make the Asia Pacific more secure. America has the strongest military in the world, but we don’t seek conflict; we seek to keep the peace. We want a future where disputes are resolved peacefully and where bigger nations don’t bully smaller nations. All nations are equal in the eyes of international law. We want to deepen our cooperation with other nations on issues like counterterrorism and piracy, but also humanitarian aid and disaster relief — which will help us respond quickly to catastrophes like the tsunami in Japan, or the typhoon in the Philippines. We want to do that together.

Together, we want to make the Asia Pacific more prosperous, with more commerce and shared innovation and entrepreneurship. And we want to see broader and more inclusive development and prosperity. Through agreements like the TPP, we want to make sure nations in the Asia Pacific can trade under rules that ensure fair access to markets, and support jobs and economic growth for everybody, and set high standards for the protection of workers and the environment.

Together, we want to make the Asia Pacific — and the world –- cleaner and more secure. The nations of this region are uniquely threatened by climate change. No nation is immune to dangerous and disruptive weather patterns, so every nation is going to have to do its part. And the United States is ready to do ours. Last year, I introduced America’s first-ever Climate Action Plan to use more clean energy and less dirty energy, and cut the dangerous carbon pollution that contributes to climate change. So we want to cooperate with countries in Southeast Asia to do the same, to combat the destruction of our forests. We can’t condemn future generations to a planet that is beyond fixing. We can only do that together.

Together, we can make this world more just. America is the world’s oldest constitutional democracy; that means we’re going to stand up for democracy — it’s a part of who we are. And we do this not only because we think it’s right, but because it’s been proven to be the most stable and successful form of government. In recent decades, many Asian nations have shown that different nations can realize the promise of self-government in their own way; they have their own path. But we must recognize that democracies don’t stop just with elections; they also depend on strong institutions and a vibrant civil society, and open political space, and tolerance of people who are different than you. We have to create an environment where the rights of every citizen, regardless of race or gender, or religion or sexual orientation are not only protected, but respected.

We want a future where nations that are pursuing reforms, like Myanmar, like Burma, consolidate their own democracy, and allow for people of different faiths and ethnicities to live together in peace. We want to see open space for civil society in all our countries so that citizens can hold their governments accountable and improve their own communities. And we want to work together to ensure that we’re drawing on the potential of all our people –- and that means ensuring women have full and equal access to opportunity, just like men.

And to make sure we can sustain all these efforts, we want a future where we’re building an architecture of institutions and relationships. For America, that always begins with our alliances, which serve as the cornerstone of our approach to the world. But we also want to work with organizations like ASEAN and in forums like APEC and the East Asia Summit to resolve disputes and forge new partnerships. And we want to cooperate with our old allies and our emerging partners, and with China. We want to see a peaceful rise for China, because we think it can and should contribute to the stability and prosperity that we all seek.

So that’s the shared future I want to see in the Asia Pacific. Now, America cannot impose that future. It’s one we need to build together, in partnership, with all the nations and peoples of the region, especially young people. That vision is within our reach if we’re willing to work for it.

Now, this world has its share of threats and challenges, and that’s usually what makes the news. We know that progress can always be reversed, and that positive change is achieved not through passion alone, but through patient and persistent effort. But we’ve seen things change for the better in this region and around the world because of the effort of ordinary people, together — working together. It’s possible. We’ve seen it in the opportunity and progress that’s been unleashed in this amazing part of the world.

I’ve only been in Malaysia for a day, but I’ve already picked up a new phrase: Malaysia boleh. Malaysia can do it. Now, I have to say, we have a similar saying in America: Yes, we can. That’s the spirit in which I hope America and all the nations of Southeast Asia can work together, and it’s going to depend on your generation to carry it forward. As Presidents and Prime Ministers, they can help lay the foundation, but you’ve got to build the future.

And now I want to hear directly from you. I want to hear your aspirations for your own lives, your hopes for your communities and your culture, what you think we can do together in the years to come.

Terima kasih banyak.

Moderator Anita Woo: Thank you very much, Mr. President. If you may?

President Obama: Well, I’m going to take the first question, and then I think Anita is going to take a question from social media. This is tough because we have so many outstanding young people. I’ll call on this young lady right here, right in the front.

Tell me your name. If you’re going to school, tell me what level you’re at, what year you are in school, and where you’re from.

Question: Hi, Mr. President. I’m from Cambodia, and I went to Institute of Foreign Languages at the Royal University of Phnom Penh. And I’ve got a very simple question for you. What was your dream when you were in your 20s, and did you achieve it? And if so, how did you achieve it?

President Obama: Well, it’s a short question but it’s not a simple one. When I was in high school — so, for those of you who are studying under a different system, when I was 15, 16, 17, before I went to the university — I wasn’t always the best student. Sometimes I was enjoying life too much. Don’t clap. This guy is the same way. No, part of it I was rebelling, which is natural for young people that age. I didn’t know my father, and so my family life was complicated. So I didn’t always focus on my studies, and that probably carried over into the first two years of university.

But around the age of 20, I began to realize that I could have an impact on the world if I applied myself more. I became interested in social policy and government, and I decided that I wanted to work in the non-profit sector for people who are disadvantaged in the United States. And so I was able to do that for three years after I graduated from college. That’s how I moved to the city of Chicago. I was hired by a group of churches to work in poor areas to help people get jobs and help improve housing and give young people more opportunity. And that was a great experience for me, and it led me to go to law school and to practice civil rights laws, and then ultimately to run for elected office.

And when I think back to my journey, my past, I think the most important thing for — and maybe the most important thing for all the young people here — is to realize that you really can have an impact on the world; you can achieve your dreams. But in order to do so, you have to focus not so much on a title or how much money you’re going to make, you have to focus more on what kind of influence and impact are you going to have on other people’s lives — what good can you do in the world.

Now, that may involve starting a business, but if you want to start a business you should be really excited about the product or the service that you’re making. It shouldn’t just be how much money I can make — because the business people who I meet who do amazing things, like Bill Gates, who started Microsoft — they’re usually people who are really interested in what they do and they really think that it can make a difference in people’s lives.

If you want to go into government, you shouldn’t just want to be a particular government official. You should want to go into government because you think it can help educate some children, or it can help provide jobs for people who need work.

So I think the most important thing for me was when I started thinking more about other people and how I could have an impact in my larger society and community, and wasn’t just thinking about myself. That’s when I think your dreams can really take off — because if you’re only thinking about you, then your world is small; if you‘re thinking about others, then your world gets bigger.

Thank you.

Moderator Woo: Thank you, Mr. President. We now have a question from the social media, which we’ve been collecting over the week.

President Obama: Okay.

Question: The question comes from our friend from Burma, from Myanmar. And he asks: To Mr. President, what would be your own key words or encouragement for each of us leaders of our next generation while we are cooperating with numerous diversities such as different races, languages, beliefs and cultures not only in Myanmar, but also across ASEAN? Thank you.

President Obama: Well, it’s a great question. If you look at the biggest source of conflict and war and hardship around the world, one of the most if not the most important reasons is people treating those who are not like them differently. So in Myanmar right now, they’re going through a transition after decades of repressive government, they’re trying to open things up and make the country more democratic. And that’s a very courageous process that they’re going through.

But the danger, now that they’re democratizing is that there are different ethnic groups and different religions inside of Myanmar, and if people start organizing politically around their religious identity or around their ethnic identity as opposed to organizing around principles of justice and rule of law and democracy, then you can actually start seeing conflicts inside those countries that could move Myanmar in a very bad direction — particularly, if you’ve got a Muslim minority inside of Myanmar right now that the broader population has historically looked down upon and whose rights are not fully being protected.

Now, that’s not unique to Myanmar. Here in Malaysia, this is a majority Muslim country. But then, there are times where those who are non-Muslims find themselves perhaps being disadvantaged or experiencing hostility. In the United States, obviously historically the biggest conflicts arose around race. And we had to fight a civil war and we had to have a civil rights movement over the course of generations until I could stand before you as a President of African descent. But of course, the job is not done. There is still discrimination and prejudice and ethnic conflict inside the United States that we have to be vigilant against.

So my point is all of us have within us biases and prejudices of people who are not like us or were not raised in the same faith or come from a different ethnic background. But the world is shrinking. It’s getting smaller. You could think that way when we were all living separately in villages and tribes, and we didn’t have contact with each other. We now have the Internet and smart phones, and our cultures are all colliding. The world has gotten smaller and no country is going to succeed if part of its population is put on the sidelines because they’re discriminated against.

Malaysia won’t succeed if non-Muslims don’t have opportunity. Myanmar won’t succeed if the Muslim population is oppressed. No society is going to succeed if half your population — meaning women — aren’t getting the same education and employment opportunities as men. So I think the key point for all of you, especially as young people, is you should embrace your culture. You should be proud of who you are and your background. And you should appreciate the differences in language and food. And how you worship God is going to be different, and those are things that you should be proud of. But it shouldn’t be a tool to look down on somebody else. It shouldn’t be a reason to discriminate.

And you have to make sure that you are speaking out against that in your daily life, and as you emerge as leaders you should be on the side of politics that brings people together rather than drives them apart. That is the most important thing for this generation. And part of the way to do that is to be able to stand in other people’s shoes, see through their eyes. Almost every religion has within it the basic principle that I, as a Christian, understand from the teachings of Jesus. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Treat people the way you want to be treated. And if you’re not doing that and if society is not respecting that basic principle, then we’re going backwards instead of going forward.

And this is true all around the world. And sometimes, it’s among groups that those of us on the outside, we look — they look exactly the same. In Northern Ireland, there has been a raging conflict — although they have finally come to arrive at peace — because half or a portion of the population is Catholic, a portion is Protestant. From the outside, you look — why are they arguing? They’re both Irish. They speak the same language. It seems as if they’d have nothing to argue about. But that’s been a part of Ireland that has been held back and is poor and less developed than the part of Ireland that didn’t have that conflict.

In Africa, you go to countries — my father’s country of Kenya, where oftentimes you’ve seen tribal conflicts from the outside you’d think, what are they arguing about? This is a country that has huge potential. They should be growing, but instead they spend all their time arguing and organizing politically only around tribe and around ethnicity. And then, when one gets on top, they’re suspicious and they’re worried that the other might take advantage of them. And when power shifts, then it’s payback. And we see that in society after society. The most important thing young people can do is break out of that mindset.

When I was in Korea, I had a chance to — or in Tokyo rather — I had a chance to see an exhibit with an astronaut, a Japanese astronaut who was at the International Space Station and it was looking at the entire globe and they’re tracking now changing weather patterns in part because it gives us the ability to respond to disasters quicker. And when you see astronauts from Japan or from the United States or from Russia or others working together, and they’re looking down at this planet from a distance you realize we’re all on this little rock in the middle of space and the differences that seem so important to us from a distance dissolve into nothing.

And so, we have to have that same perspective — respecting everybody, treating everybody equally under the law. That has to be a principle that all of you uphold. Great question. Let me call on the — I’m going to go boy, girl, boy, girl so that everybody gets a fair chance. Let’s see, hold on. This gentleman right here, right there with the glasses. There you go.

Question: Hello, Mr. President.

President Obama: Hello.

Question: I’m from Malaysia, currently with YES Alumni Malaysia. Well, I have a question. I wondered what was your first project — community service project that you didn’t like and how did the project impact your community? Thank you so much.

President Obama: That’s a great question. I told you that when I graduated from college, I wanted to work in poor neighborhoods. And so, I moved to Chicago and I worked. This community had gone through some very difficult times. The steel plants there, the steel mills had closed. A lot of manufacturing was moving out of America or becoming technologically obsolete, these old mills. And so, these were areas that had been entirely dependent on steel. And as those jobs left, the communities were being abandoned.

And there was also racial change in the area. They had been predominantly white, and then blacks and Latinos had moved in. And there was fear among the various groups. So they had a lot of problems. I will tell you this, what I did was I organized a series of meetings listening to people to find out what they wanted to do something about first. The most immediate problem they saw was there was a lot of crime that had emerged in the area, but they didn’t quite know how to do anything about it. So I organized a meeting with the police commander, so that they could file their complaints directly to the police commander and try to get more action to create more safe space in those communities for children and to end people standing on street corners, because it was depressing the whole community.

Now, here’s the main thing I want to tell you. That first meeting, nobody came. It was a complete failure and I was very depressed, because I thought, well, everybody said that they were concerned about crime, but when I organized the meeting nobody came. And what it made me realize is, is that if you want to bring about change in a community or in a nation it’s not going to happen overnight. Usually, it’s very hard to bring about change, because people are busy in their daily lives. They have things to do. One of the things I realized was I hadn’t organized the meeting at the right time. It was right around dinner time, and if people were working they were coming home and picking up their kids, and they couldn’t get to the meeting fast enough.

So, first of all, you’ve got to try to get people involved. And a lot of people are busy in their own lives or they don’t think it’s going to make a difference or they’re scared if they’re speaking out against authority. And many of the problems that we’re facing, like trying to create jobs or better opportunity or dealing with poverty or dealing with the environment, these are problems that have been going on for decades. And so, to think that somehow you’re going to change it in a day or a week, and then if it doesn’t happen you just give up, well, then you definitely won’t succeed.

So the most important thing that I learned as a young person trying to bring about change is you have to be persistent, and you have to get more people involved, and you have to form relationships with different groups and different organizations. And you have to listen to people about what they’re feeling and what they’re concerned about, and build trust. And then, you have to try to find a small part of the problem and get success on that first, so that maybe from there you can start something else and make it bigger and make it bigger, until over time you are really making a difference in your community and in that problem.

But you can’t be impatient. And the great thing about young people is they’re impatient. The biggest problem with young people is they’re impatient. It’s a strength, because it’s what makes you want to change things. But sometimes, you can be disappointed if change doesn’t happen right away and then you just give up. And you just have to stay with it and learn from your failures, as well as your successes.

Anita.

Moderator Woo: Mr. President, thank you very much. We have a question from our friend in Singapore. He asks, what is the legacy you wish to leave behind?

President Obama: I’ve still got two and a half years left as President, so I hope he’s not rushing me. But what is true is that as President of the United States, you have so many issues coming at you every day, but sometimes I try to step back and think about 20 years from now when I look back what will I be most proud of or what do I think will be most important in the work that I’ve done.

Now, my most important legacy is Malia and Sasha, who are turning out to be wonderful young people. So your children, if you’re a parent the most important legacy you have is great children — and I have those — who are happy and healthy, and I think they’re going to do great things. Another important legacy is being a good husband. So I’ve tried to do that. That’s important, because if you don’t do those things well, then everything else you’re going to have some problems with.

But I think as President, what I’ve tried to do in the United States is really focus on how do you create opportunity for all people. And when I first came into office, we were in a huge financial crisis that had hit the entire world. And it was the worst crisis the United States had had since the 1930s. So the first thing I had to do was just make sure that we stop the crisis and start allowing the economy to recover. And we’ve now created more than 9 million jobs and the economy is beginning to improve for a lot of people. But what you’ve also seen is a trend in the United States but also around the world in which even when the economy grows, it tends to benefit a lot of people at the very top, but the vast majority of people, they don’t benefit as much. And you’re starting to see bigger and bigger gaps in inequality and in wealth and in opportunity.

And that’s true not just in the United States, it’s true in Europe; it’s long been true in parts of Asia; it’s been true in Latin America. And I believe that economies work best when growth and development is broad-based, when it’s shared — when ordinary people, if they work hard and they take responsibility, they can succeed. Not everybody is going to be rich, but everybody should be able to live a good life. Not everybody is going to be a billionaire, but everybody should be able to have a nice home and educate their children and feel some sense of security.

So that’s not something that I can do by myself as President of the United States, but everything that I do — whether it’s providing more help for people to go to college, or giving early childhood education to young children because we know that the younger children get some additional schooling, especially poor children, the better off they’ll do in school for all the years to come, to the work that we’re trying to do in providing health care for all Americans so that they don’t experience a crisis when somebody in their family gets sick — all of those efforts are with the objective of making sure that ordinary people, if they work hard and act responsibly, they can succeed.

And internationally, my main goal has been to work with other partners to promote a system of rules so that conflicts can be resolved peacefully, so that nations observe basic rules of behavior, so that whether you’re a big country or a small country, you know that there are certain principles that are observed — that might doesn’t just make right, but that there’s a set of ideals and there’s justice both inside countries and between countries.

Now, that means trying to end the proliferation of nuclear weapons, which are a threat to humanity. And we’ve made progress in that front, me negotiating the reduction of our nuclear stockpiles with the Russians, and trying to resolve through diplomacy the problem that Iran has been trying to pursue nuclear weapons, and working with countries like Malaysia to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

That means working to get chemical weapons out of Syria. It means trying to promote a just peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians. It means opening up to Burma. And I was the first President to visit there, and seeing if we could take advantage of the opportunity with Aung San Suu Kyi’s release to create a country that was a responsible part of the world order.

Sometimes our efforts have been successful; sometimes, as I told this young man here, my efforts initially haven’t been as successful and I’ve had to keep on trying. And I am confident that when I’m done as President there’s still going to be parts of the world that are having war, that are having conflict, that are oppressing their own people. So I’m not going to solve all these problems. I’ve got to leave some work for all of you.

But what I do hope is that I will have made progress on each of those fronts — that if when I leave I can say there are a few more countries that are democracies now and the United States helped; if there are countries where I can say — or areas of the world where I can say we avoided conflict between two countries because we helped to mediate a dispute, I’ll be proud of that. If there are countries where a spotlight has been shined internationally on the oppression of a minority group and it has forced that country to change its practices, that will be a success.

I don’t consider — I don’t think I can do that by myself, of course. I can only do that not only with the cooperation and consultation of other leaders, but it’s also other citizens of the world — all of you and people in various regions, they’ve got to want more justice and more peace in order for us to achieve it.

Sometimes the United States is viewed as, on the one hand, the cause of everybody’s problem, or on the other hand, the United States is expected to solve everybody’s problem. And we are a big, powerful nation and we take our responsibilities very seriously, but we can only do so much. Ultimately, the people in these countries themselves have to partner with us — because we have problems in our own country that we have to solve. But hopefully, I’m also lifting up certain universal principles and ideals that all of us can embrace and share.

All right, it’s a woman’s turn. It’s a young woman’s turn. I’ve got to — let’s see who is back here. No, it’s a young lady’s turn. Okay, this young lady right here — since the microphone is right there.

Question: Good afternoon, Mr. President, and welcome to Malaysia. Gathering from what you’ve said, I think it’s a shared consensus that youth worldwide can be the catalyst, planting the seeds for an early conditioning on certain global issues here. So my question is how exactly can America lead us youth internationally in championing such issues, for example, climate change, women empowerment, poverty eradication — the goal being to bring the human race together? It appears that a lot of policies have been put in place, but a lot of the policies that have been put in place by the Gen Xers, the Baby Boomers. People like us, the Gen Ys, we don’t have a say in this policy, so we are supposed to champion them, but how are we supposed to do all these things?

President Obama: I’m trying to figure out which generation I am. You got Baby Boomers, then Gen X, and then there’s a Gen Y — we’re on Y? Is that Z, are they here yet, or — that’s next?

Well, first of all, just to be very specific, as I said in my speech, part of the reason that I like to meet with young people is to get their suggestions and their ideas. But then what we try to do is set up a process and a network of young leaders who can share ideas with each other and with us, to let us know how they think we can empower you.

So coming out of this meeting, there will be mechanisms through social media and in our embassies in each of the 10 ASEAN countries where we’re going to be bringing together youth leaders to talk to each other about their plans, what their priorities are, how they think the United States can be most helpful. And we’re going to take your suggestions.

And let’s take the example of something like climate change. The voice of young people on this issue is so important because you are the ones who are going to have to deal with the consequences of this most significantly. I rode with Prime Minister Najib from our press conference to the new MaGIC Center that’s been set up — entrepreneurial center that came out of our global entrepreneur summit that was hosted here in Malaysia. And on the ride over, it hadn’t started raining yet, but you could tell it was going to be raining soon. And he said that here in Malaysia you’ve already seen a change in weather patterns — it used to be that the dry season and the rainy season was very clear. Now it all just kind of is blurring together.

Now, not all of that can be directly attributed precisely to climate change. But when you look at what’s been happening all across the country or all around the world, there’s no doubt that weather patterns are changing. It is getting warmer. That is going to have impacts in terms of more flooding, more drought, displacement. It could affect food supplies. It could affect the incidences of diseases. Coastal communities could be severely affected. And what happens when humans are placed under stress is the likelihood of conflict increases.

There is a theory that one of the things that happened in Syria to trigger the protests that resulted in the terrible, violent efforts to suppress them by President Assad was repeated drought in Syria that drove people off their land, so they could no longer afford to make the traditional living that they had made. Now, whether that’s true or not we don’t know precisely. But what we do know is that you see in communities that are under severe weather pressure — drought, famine, food prices increasing — they’re more likely to be in conflict.

And you’re going to have to deal with this, unless we do something about it. So the question is what can we do? Every country should be coming up with a Climate Action Plan to try to reduce its carbon emissions. In Southeast Asia, one of the most important issues is deforestation. In Indonesia and Malaysia, what you’ve seen is huge portions of tropical forests that actually use carbon and so reduce the effects of climate change, reduce carbon being released into the atmosphere and warming the planet — they’re just being shredded because of primarily the palm oil industry. And there are large business interests behind that industry.

Now, the question is are we going to in each of those countries say how can we help preserve these forests while using a different approach to economic development that does less to damage the atmosphere? And that means engaging then with the various stakeholders. You’ve got to talk to the businesses involved. You’ve got to talk to the government, the communities who may be getting jobs — because their first priority is feeding themselves, so if you just say, we’ve got to stop cutting down the forests, but you don’t have an alternative opportunity for people then they may just ignore you. So there are going to be all kinds of pieces just to that one part of the problem. And each country may have a different element to it.

The point, though, is that you have to be part of the solution, not part of the problem. You have to say, this is important. You don’t have to be a climate science expert, but you can educate yourselves on the issue. You can discuss it with your peer groups. You can organize young people to interact with international organizations that are already dealing with this issue. You can help to publicize it. You can educate your parents, friends, coworkers. And through that process, you can potentially change policy.

So it may take — it will take years. It will not happen next week. But our hope is that through this network that we’re going to be developing that we can be a partner with you in that process.

So I just want to check how many — how much time do we have here? Who is in charge?

Moderator Woo: We’ve got time, Mr. President.

President Obama: How much time?

Moderator Woo: A couple more questions.

President Obama: A couple more questions — all right, because I just want to make sure that I’m being fair here. All right, it’s a guy’s turn. Let’s see — all right, how about this guy, because I like his hair cut, the guy with the spiky hair right there.

Question: In your opinion, what are the top three advice to fellow Malaysians and government to become a developed country in six years’ time? As this is one of country’s missions and I think it’s important for fellow Malaysians to contribute together in order to achieve that. Thank you.

President Obama: Well, I had an extensive conversation with Prime Minister Najib about his development strategy. First of all, Malaysia is now a middle-income country. It’s done much better than many other countries in per capita income and growth over the last two decades, and there’s been some wise leadership that has helped to promote Malaysian exports and to help to train its people.

You’ve got high literacy rates, which is critically important. Investing in people is the single most important thing in the knowledge economy. Traditionally, wealth was defined by land and natural resources. Today the most important resources is between our ears. And Malaysia has made a good investment in young people. So that continues to be I think the most important strategy for growth in the 21st century.

And in the United States, my main focus is improving our education system and lifelong learning. Because part of what’s changed in the economy — in the 20th century, you got a change at a company, you might stay there for 30 years; things didn’t change that much. Now you may be at one company and that company may be absorbed, and you might have to retrain for a new job because the thing that you were doing before has been made obsolete because of technology.

So we have to keep on investing in not only elementary school and secondary school and even universities. But in the United States, for example, we have a system of community colleges and job training where somebody who’s in their 30s or even 40s or 50s can go back, get retrained, get more skills, adapt to a new industry, and then be a productive citizen. That’s a critical investment that needs to be made.

The second thing that I know Prime Minister Najib is focused on — and this applies throughout the region — is if you want to move to the next level of development, then you have to open up an economy to innovation and entrepreneurship. The initial push for growth in Southeast Asia initially started with exporting raw materials, and then shifted to manufacturing and light assembly and being part of the global supply chain. And that’s all a very important ladder into development. But now a lot of wealth is being created by new products and new ideas.

And at least in the United States, for example, we don’t want to just assemble the latest smartphone, we want to invent the latest smartphone. We want to invent the apps and the content for those smartphones. And then we have an asset that whoever is manufacturing it, some of the value is still flowing to us. Well, what that requires then is changes in the economy to make it more open, to make it more entrepreneurial. Some of the old systems have to be broken down.

Now, different countries in ASEAN and different countries around the world are at different stages of development. In some countries, the most important thing for development is just basic rule of law, and something that I said earlier, which is making sure that the law applies to everybody in the same way. I believe if Malaysia is going to take that next leap, then it’s going to have to make sure that the economy is one where everybody has the opportunity, regardless of where they started, to succeed. And that energy has to be unleashed. And I think Prime Minister Najib understands that.

And the trade agreement that we’re trying to create, the TPP, part of what we’re trying to do is to create higher standards for labor protection, higher standards for environmental protection, more consistent protection of intellectual property — because increasingly that’s the next phase of wealth. All those things require more transparency and more accountability and more rule of law, and I think that it’s entirely consistent with Malaysia moving into the next phase.

Now, it’s hard to change old ways of doing things — and that’s true for every country. I mean, China right now, after unprecedented growth over the last 20 years, realizes it’s got to change its whole strategy. It’s been so export-oriented, but now they’re starting to realize that if they want to continue to grow they’ve got to develop consumer markets inside their own country.

And what that means is, is that they’ve got to give workers more ability to spend on consumer goods, and that they have to have a social safety net so that workers aren’t just saving all the time, because if they get sick they don’t have any social insurance programs and they don’t have any retirement groups. And so they’re starting to make these shifts, but these are hard shifts.

Even in a country that’s controlled by the central party that’s not democratic. It’s because certain people have gotten accustomed to and done very well with an export-driven strategy. So when you shift, there’s going to be somebody who resists. That’s true in every country. It’s true in the United States. We’ve got to change how we do things. And when you try to change, somebody somewhere is benefiting from the status quo. Malaysia is no different. But I’m confident that you can make it happen.

I’ll take two more questions. And it’s a young lady’s turn. So, guys, you can all put down your hands. Let’s see — this young lady with the yellow.

Question: Good morning. I’m from Indonesia.

President Obama: Apa kabar?

Question: Baik-baik saja.

President Obama: Baik.

Question: Well, okay, I have a very short question. What does happiness mean for you?

President Obama: What does happiness mean to me?

Question: Yes.

President Obama: Wow, you guys — that’s a big, philosophical question. I mentioned earlier my family, and it really is true that the older I get the more — when I think about when I’m on my deathbed — I mean, I don’t think about this all the time. I don’t want you to think — I’m still fairly young. But when I think, at the end of my life and I’m looking back, what will have been most important to me, I think it’s the time I will have spent with the people I love. And so that makes me happy.

But I also think that, as I get older, what’s most important to me is feeling as if I’ve been true to my beliefs and that I’ve lived with some integrity. Now, that doesn’t always make you happy in the sense of you’re laughing or just enjoying life — because sometimes, being true to your beliefs is uncomfortable. Sometimes doing things that you think are right may put you in some conflict with somebody. Sometimes people may not appreciate it and it may be inconvenient.

But I think that part of being satisfied at least with life as you get older is feeling as if you know that every day you wake up and there’s certain things you believe in — for example, respecting other people, or showing kindness to others, or trying to promote justice, or whatever it is that you think is best in you — that at the end of each day you can say, okay, you know what, I was consistent with what I say I’m about, what I say I believe in — the image I have of myself.

And when I’m uncomfortable is when I think, you know, I didn’t do my best today. Maybe I didn’t speak out when I should have spoken out. Maybe I didn’t work as hard on this issue as I should have worked. Then I’m tossing and turning and I don’t feel good.

And I think that having that kind of integrity is important — where you can look at yourself in the mirror and you can say, okay, I am who I want — who I say I want to be. And nobody is perfect and everybody is going to make mistakes, but I think if you feel as if you’re always striving towards your ideals, then you’ll feel okay at the end.

Okay, last question. And it’s — let’s see. No, no, it’s a guy’s question. Women, put down your hands. Okay, I’ll call on this gentleman here because he — there you go, with the glasses.

Question: Good evening, Mr. President Obama. I’m from Malaysia. I’m an undergrad from University of Malaya. So my question is, in your position right now, what values that you uphold the most that you think is very important, that makes you what you are today? And what do you wish to bring that value to the young people of today that can change the world to become a better world? Thank you.

President Obama: Well, thank you. I’m going to take another question after that, because I’ve already answered this question. Wait, wait, wait — let me — let me explain the — what I think is most important is showing people respect who you disagree with, right? And so, for example, there’s a note over there — I don’t know what those young people are putting a note about — but I think that the basic idea that if somebody is not like you, if they look differently than you, if they believe differently than you — that you are treating them as you want to be treated. If you are applying those ideas, I think you’re going to be halfway there in terms of solving most of the world’s problems.

And a lot of that is around some of the traditional divisions that we have in our society — race, ethnicity, religion, gender. Treat people with respect, whoever they are, and expect your governments to treat everybody with respect. And if you do that, then you’re going to be okay.

All right, last question. Young ladies — wait, wait, wait, everybody put down their hands for a second. Okay, now I’ve heard from — I’ve had an Indonesian, a Malaysian, a Cambodian, Myanmar. Thailand didn’t get called on. So I think — all right, Thailand. Where — okay. And the Philippines — well, see, I can’t call on everybody. Thailand said — they were the first ones to shout. Go ahead, this young lady right here.

Question: Hi, President. Very short question. What are the things that you regret now that you have done in the past?

President Obama: What are the things that I regret? Oh, the list is so long. I regret calling on you, because now I’m going to be telling everybody my business. No, I’m just joking about that.

I’m now 52. And I still feel pretty good. I’m a little gray-haired. But I will tell you two things I regret — one is very specific, one is more general. The specific thing is I regret not having spent more time with my mother. Because she died early — she got cancer right around when she was my age, actually, she was just a year older than I am now — she died. It happened very fast, in about six months. And I realized that — there was a stretch of time from when I was, let’s say, 20 until I was 30 where I was so busy with my own life that I didn’t always reach out and communicate with her and ask her how she was doing and tell her about things. I was nice and I’d call and write once in a while. But this goes to what I was saying earlier about what you remember in the end I think is the people you love. I realized that I didn’t — every single day, or at least more often, just spend time with her and find out what she was thinking and what she was doing, because she had been such an important part of my life.

Now, that’s natural as young people. As you grow up, you become independent. But for those of you who have not called their parents lately, I would just say that that is something, actually, that I regret.

The more general answer is I regret wasting time. I think when I was young I spent a lot of time on things that I realize now were not very important and I wish I had used my time more wisely.

Now, I don’t want people to spend every minute of every day working all the time, because you have to enjoy life and you have to have friends and you have to appreciate all that life has to offer. But I do think that in America at least, but now I think worldwide, we spend an awful lot of time on diversions — watching TV or playing video games. And all that time, when you add it all up, I say to myself, I could have spent more time learning a foreign language, or I could have spent more time working on a project that was important. And I think it would be useful for all of you to consider how you’re spending your time and make sure that you’re making every day count.

Let me just say this by way of thank you to all of you. I think you’ve asked terrific questions. I’m so impressed with all of you and what you have done and what you’ll do in the future. I do want you to feel optimistic about your future. Even though I told you about some problems like climate change that seem so big now, I always say — we get White House interns to come in and they work at the White House, and they’re there for six months, and then I usually speak to them at the end of six months. And I always tell them that despite how hard sometimes the world seems to be, and all you see on television is war and conflict and poverty and violence, the truth is that if you had to choose when to be born, not knowing where or who you would be, in all of human history, now would be the time. Because the world is less violent, it is healthier, it is wealthier, it is more tolerant and it offers more opportunity than any time in human history for more people than any time in human history.

Now, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t still terrible things happening around the world or in this region. We still have things like human trafficking. And we still have terrible abuse of children. And there are conflicts. And so these are things that we’re going to have to tackle and deal with. But you should know that with each successive generation things have improved just a little bit. And over time, that little bit adds to a lot. And it’s now up to you, the next generation, to make sure that 20 years from now, or 30 years from now, people look back and say, wow, things are a lot better now than they were back then.

And there will still be problems 20 or 30 years from now also. But they will be different problems, because you will have solved many of the problems that exist today. And America wants to be a partner with you in that process, so good luck.

Thank you, everybody.

Moderator Woo: Thank you very much, Mr. President. It’s been a wonderful opportunity and we appreciate it very much.

President Obama: Thank you, everybody.

Want to learn more about storytelling? Start by downloading the first chapter of The Storytelling Mastery.