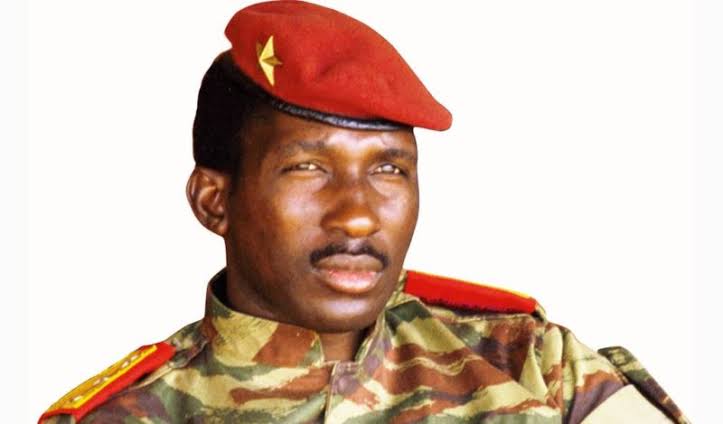

Thomas Sankara – Yes. We must dare to invent the future

Unlike many, the former president of Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara was one of the few Pan-Africanists to gain power in postcolonial Africa, and to wield it for the good of the people. Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara was a Burkinabé military officer and socialist revolutionary who served as the President of Burkina Faso from his coup in 1983 to his deposition and killing in 1987. He is regarded as one of the best revolutionary leaders in modern African history both for his strong charisma and his people-oriented leadership.

Download the first chapter of The Storytelling Series: Beginners’ Guide for Small Businesses & Content Creators by Obehi Ewanfoh.

A little over 31 years ago, in October 1987, the president of Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara, was murdered in a coup instigated by his former friend and army captain Blaise Compaoré. Compaoré went on to become president, a position he retained until some four years ago, when, in October 2014, he was overthrown by a popular uprising.

Burkina Faso had endured 27 years of Compaoré’s tyranny, but when he tried to change the constitution and run for a fifth presidential term, the people had finally had enough. This time, not even his long-term minder, the French state, could save its puppet. Compaoré fled to another West African country with French tentacles all over it, the Ivory Coast.

Here is another article you might like – Thomas Sankara – Yes. We must dare to invent the future

It should be remembered that the elections Compaoré won were such in name only. They came in 1991, 1998, 2005 and 2010 – irregularly, and far from free and fair. They consolidated the odious power of a politician who followed a policy of so-called rectification of Sankara’s progressive agenda. Compaoré was the Jair Bolsonaro to Sankara’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, with the difference that, unlike Lula’s Workers’ Party, not a whiff of scandal or corruption clung to Sankara.

Sankara was two months short of his 38th birthday when he and a dozen of his bodyguards and aides were assassinated. He had led Burkina Faso for little more than four years, from August 1983, when Compaoré marched 250 soldiers into the capital, Ouagadougou, leading to the removal of the previous president, Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo. Sankara was made president of the National Council of the Revolution, a body which, under his guidance, lived up to its name.

These reforms and programmes were lazily labelled as if they were crudely leftist, both by the country’s landed and merchant classes, and by the imperialist West. Despite paying homage to revolutions in the West, and in particular the French and American ones, Sankara was not popular in the capitals of the Bretton Woods nations. Memorably, at the UN in 1984, he invoked a significant moment in French history, saying, “The French Revolution of 1789, which overturned the foundations of absolutism, taught us the connection between the rights of man and the rights of peoples to liberty.”

The people shall govern

Sankara was one of the few Pan-Africanists to gain power in postcolonial Africa, and to wield it with the good of the people in mind. The breadth and depth of his agenda were astonishing. In contrast to most political theorists and almost all practising politicians, Sankara believed in the ability of the people to govern. Thus it was that he drew on organisations that mobilised the youth, peasant farmers and workers to help carry out his reforms. The people of the former Upper Volta were harnessed in a great national project: young and old, women and men, artisans and farmers. The new name of the country laid out its credo: Burkina Faso, meaning “land of incorruptible people”, was adopted in 1984.

To advance and inspire the revolution, Sankara gave inspiring speeches (and interviews) at home and abroad. In some, he took the guise of intellectual and theorist, in others the role of galvanizer of the people. Here are excerpts from some of them, representing Sankara the inspirational force. They focus on the emancipation of women and the Burkinabè revolution. (Excerpts from Thomas Sankara Speaks, Pathfinder Press, 1988.)

From the end of a lengthy interview with Swiss journalist Jean-Philippe Rapp in 1985:

Sankara: “You cannot carry out fundamental change without a certain kind of madness. In this case, it comes from nonconformity, the courage to turn your back on the old formulas, the courage to invent the future. Besides, it took the madmen of yesterday for us to be able to act with extreme clarity today. I want to be one of those madmen.”

Rapp: “To invent the future?”

Sankara: “Yes. We must dare to invent the future. In the speech I gave launching the five-year plan, I said, ‘Everything man is capable of imagining, he can create.’ I’m convinced that’s true.”

From his Political Orientation speech, October 1983:

“The genuine emancipation of women is one that entrusts responsibilities to women, that involves them in productive activity and in the different fights the people face. The genuine emancipation of women is one that compels men to give their respect and consideration.”

From a speech marking the fourth anniversary of the Political Orientation speech, October 1987, just 13 days before he was killed:

“As long as the revolution cannot bring material and moral happiness to our people, it will be no more than the activity of a bunch of people – a collection of people of some merit or other – but really just a bunch of mummies who represent nothing but a lifeless collection of decaying values, incapable of moving and driving forward, incapable of transforming the reality we confront. The revolution is happiness. Without happiness, you cannot talk about success.”

Source: Newframe.com

Download the first chapter of The Storytelling Series: Beginners’ Guide for Small Businesses & Content Creators by Obehi Ewanfoh.