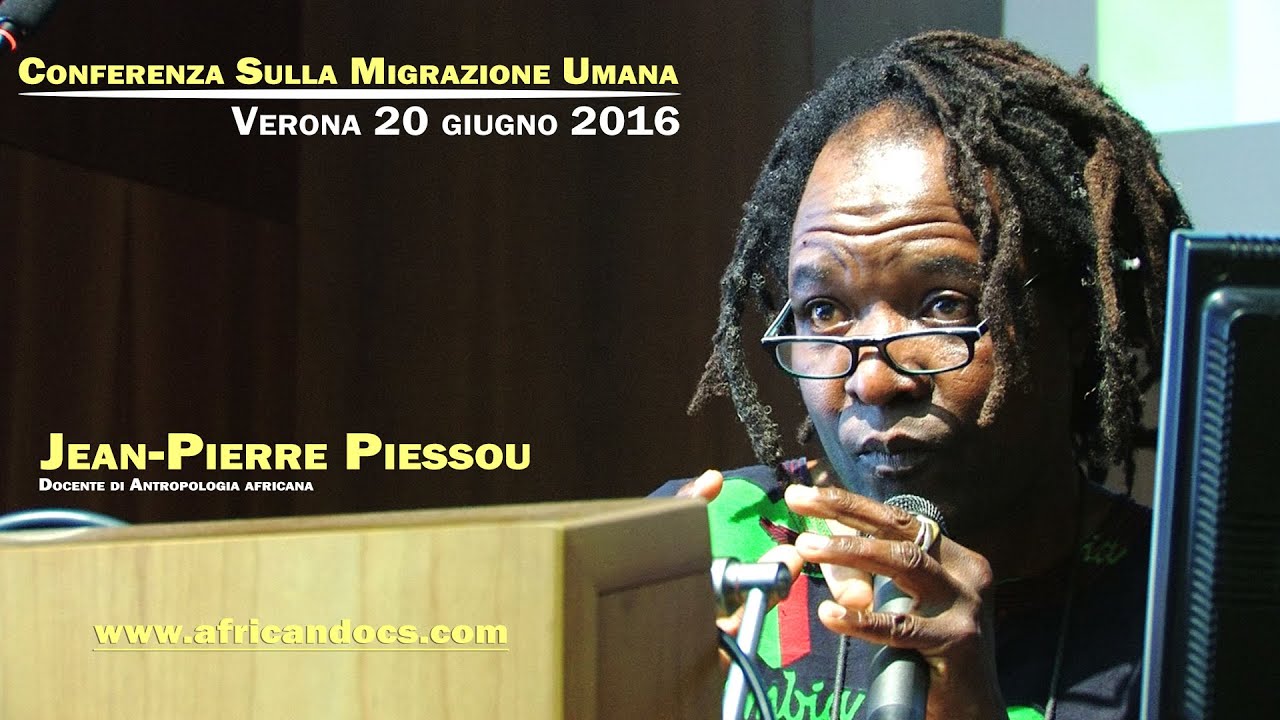

Jean-Pierre Piessou, Cultural Anthropology on WeRefugees Conference at the University of Verona

On June 20, 2016, a pivotal conference was held in Verona to mark World Refugee Day, serving as the culmination of “WeRefugees – Verona 2016”, a section of “The Journey” research project. Orchestrated by Obehi Ewanfoh, a Legacy Story Consultant and host of the Obehi Podcast, in collaboration with the University of Verona’s Department of Cultures and Civilizations, the event brought together a diverse assembly of stakeholders. Attendees included government officials, journalists, academic professors, and immigrant leaders, all gathered to dissect the complex reality of immigration in Verona and Northern Italy.

Learn How to Leverage Your Story through our Story To Asset Framework

This gathering was the final chapter of the WeRefugees – Verona 2016 initiative, a project born from Ewanfoh’s foundational research that began in 2012, focused on documenting the lived experiences of Africans in the region since the mid-1970s. What follows is the presentation by Jean-Pierre Piessou.

The Speech by Jean-Pierre Piessou (Translated from Italian to English)

World Refugee Day, today’s observance, was created and established in 1951. It was not intended as a day to celebrate someone or a special event, but to remember, because without memory, history has no meaning. In 1951, of the 54 or 55 African countries, perhaps only two were independent, Liberia and Ethiopia; all others were colonized.

Consequently, these colonized countries could not participate in the day organized by the UN to have their say or to recount their conditions. This would only happen years, or rather decades, later.

Many years passed between 1951 and 2016. Only starting in the 1960s did some countries begin the road to independence, some involving heavy bloodshed, like Algeria. Now, in the last 4 or 5 years, we find ourselves in a situation that I won’t call an “emergency,” but rather dramatic.

Dramatic because we Africans, and later it will be the turn of Syrians, Pakistanis, Afghans, continue to bury our dead. Even among the youth, there are so many deaths. So many nameless deaths.

See also We Refugees – Verona 2016: Reclaiming the Human Side of Migration

For my intervention this afternoon, I want to take this angle; I want to start from here to think of a more organic, structured project. But to create a structured project, one must give a historical reading of the situation.

The History of Asylum

To understand what asylum is, we must look at the condition of the refugee and the asylum request. Many historical figures have sought the protection of asylum, Victor Hugo, for example, fled and requested it. Even more recently, General De Gaulle requested an asylum in London in 1940 during World War II.

So, it is not a novelty. When “great men” ask for asylum, it creates no clamor. But when the “little people” do it, seeking a place to protect themselves, to recover their energy, to regenerate then it becomes a problem.

This is what we are experiencing today. From my perspective, the interpretation we give today is insufficient to understand why this is happening. it is a “fragmented,” “divided,” and partial interpretation: humanitarian, subsidiary, refugee, economic refugee. What does “economic refugee” even mean?

For example, a Nigerian who left home 8 years ago to move to Libya, to work and build a life there, finds himself facing the Libyan crisis. He must flee and find another place to go; he cannot go back, he cannot go left into Tunisia, he cannot go right into Egypt, and so he cries out for help. There is his cry.

RUAH: The Breath of the Migrant

The title of today’s intervention is “The Breath of the Migrant.” RUAH, which in Hebrew means the breath of life, the “puff” of life—that breath that God gave to Adam so he could begin to breathe. When the Earth began to breathe. The immigrant has this. However, it starts first with a cry. We hear the cry loudly, but sometimes these cries fade away. Yet, from those cries, we must recover breath. And life.

There are many people here today, many outside, many outside the reception centers, or living in the forests around the cities. Often because the commission rejected their asylum request, they were expelled from the centers and find themselves living wherever they can in the city, some even near the cemetery in Verona.

Regarding the “breath of the migrant,” I have identified some key elements: asylum, poverty, the concept of asylum-in-exile (the sense of distance), war, and the path from the noise of war to the sounds of peace.

The exodus and flight present in the Bible also affected other populations like those of the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, etc. To restore the migrant’s breath, to ensure they recover their life, it is necessary to get closer. So, my first invitation is to get closer. To talk more.

Thank you, Ewanfoh, for the documentary; it will certainly be enriched by the stories of the asylum seekers.

The Empty Suitcase and Internal Traditions

The “breath of the migrant” starts without a suitcase. Remember that during their crossing, they are stripped of everything: their suitcase, their phone, everything they have. Therefore, their suitcase is empty; this is the meaning of the open but empty suitcase.

You might also like The Architect and Open Door: Pierluigi Grigoletti on Veronetta – New Faces Of a Neighborhood

But in their breath, there is also something they carry inside, something engraved in them, and here I speak of African immigrants, who bring their traditions with them, embedded “under their skin.”

They do not leave entirely empty; they bring something belonging to their country of origin. Sometimes they even leave with a passport, which they sometimes throw away to avoid being constantly interrogated: “Where are you from? Nigeria, Gambia, Niger?”

Consider the objects considered most precious. I have included two here, though it may seem strange: the bicycle and the radio. These are two objects of happiness. I present these objects because I don’t want to waste today speaking of grand discourse.

At this point, we can no longer speak only of “welcome” in terms of food and lodging; we must speak of integration, an integration I would define as industrious or active.

This allows the migrant to search for their breath to know where they come from, where they are, and what is waiting for them. To do this, they need to be reconnected to their world of origin, not to be driven back, but to remember their roots. This memory also passes through certain objects.

In an integration project, for instance, it is important to recover objects—emphasizing the concept that bicycles can be repaired, not thrown away. That they can be salvaged, fixed up, and given as gifts, thus valuing the concept of the “gift.”

Holistic Anthropology

On a day like this, it is also important to remember one’s belonging without regret or too much nostalgia. It is important not to forget or deny one’s country of origin. Certainly, there may be war or hardship in those countries, but it is important to provide an anthropological reading through the lens of African anthropology.

African anthropology does not see a separation between the subject and the world they live in; it is a holistic and cosmic anthropology. It recovers the entire subject. There are no separations between soul, body, intellect, and mind. It contemplates the subject with their world, their vicissitudes, their objects, and their memory.

This is why I speak of these things today; though they may seem superfluous, they are vital for an asylum seeker. It is important not to deny Africa, because those who deny Africa tend also to deny the Europe and Italy that welcome them.

Recovering the idea of Africa means recovering its specific aspects: the sounds of the world you come from, the greetings, the gestures that matter in African culture. Gestures of greeting, friendship, and relationships are gestures that must be recovered on this meaningful Refugee Day.

The Reality of Migration within Africa

In this great continent, until a few years ago, there were only four economic poles toward which Africans moved for work: South Africa, Ivory Coast, Gabon, and Libya. Migrating from Nigeria or Ghana to Gabon is like migrating to Paris, these are important places of work. When these poles closed for various reasons, Ivory Coast due to war, South Africa for racial reasons (after Mandela, etc.), a void was created.

See also Turning Labels into Power for Diasporans: Moustapha Wagne on Veronetta – New Faces of a Neighborhood

Specifically, after Mandela left the political scene, a vacuum was created both as an economic pole and as a moral reference. At that moment, only one remained: Gaddafi. Gaddafi traveled to all African countries to meet young people, to talk to them, and to become the leader of the African movement.

He did this by offering money, opening Quranic schools, buying hotels, and telling university students, “If you need work, come to Libya.” He traveled across Africa and even created an airline to compete with Air France. This caused many Africans to look toward Libya, excluding other economic poles.

They moved along three routes:

- From Mali through Algeria to Libya.

- From Benin, Burkina Faso, and Niger to Libya.

- From Somalia and Kenya toward Sudan and into Libya.

Libya became a magnet; there was work for everyone, literate or illiterate. Everyone had something to do. They moved to Libya not to come to Europe, but because they were convinced, they could find the solution to their problems there. To complete that first stage toward Libya, one must cross the Sahara Desert.

I won’t dwell on this, but it would be useful to help people process memory and mourning there are more deaths in the Sahara Desert than in the Mediterranean Sea. This processing could help many asylum seekers stand on their own feet and move forward for themselves and for those who didn’t make it.

I close with the words of Master Turoldo, a master of Italian and world culture:

Sing the dream of the world

Love

Greet the people

Give

Forgive

Love again and greet.

Love

Give your hand

Help

Understand

Forget

And remember

Only the good.

And in the good of others

Rejoice and bring joy.

Rejoice in the nothing you have

In the little that is enough

Day after day:

And even that little

—if necessary—

Divide.

And go, go lightly

Behind the wind

And the sun

And sing.

Go from village to village

And greet everyone

The black, the olive-skinned

And even the white.

Sing the dream

Of the world

That all countries

May compete

To have fathered you.

And I would add: as a refugee, may they compete for you, and embrace you.

Thank you.

Conclusion: Beyond the Label, Into the Breath

Ultimately, the insights shared by Professor Piessou and the foundational research of “The Journey” remind us that a refugee is never defined solely by their displacement, but by the profound “breath of life”, the Ruah, that they carry across borders.

By moving past the sterile, “fragmented” categories of legal and economic labels, we are challenged to see the migrant as a whole person: a bearer of ancient traditions, a survivor of the silent sands of the Sahara, and an individual seeking not just a roof, but a sense of “industrious integration.”

As we reflect on these stories, we are called to move closer, to listen more, to repair what is broken, and to recognize that in welcoming the “other,” we are actually preserving the very humanity that connects us all.

The legacy of the 2016 Verona conference serves as a timeless call to action. It asks us to ensure that the “suitcases” of those arriving, though physically empty, are filled with the dignity of their origins and the promise of a shared future.

In the words of the poet Turoldo, let us “sing the dream of the world” where every country contends to claim the migrant as their own, transforming a journey of survival into a story of belonging. When we choose to see the person behind the petition, we don’t just provide asylum; we restore the breath of life to our collective history.