The $24 Trillion Deception: Why the 1883 King Leopold Plan Still Runs Africa Today

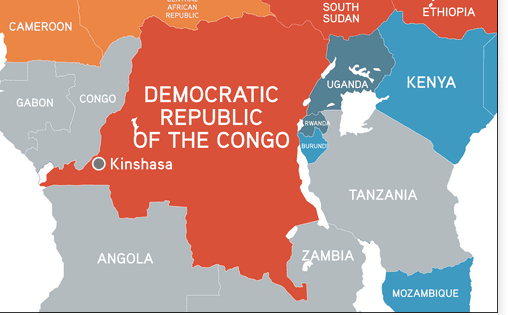

Few global contradictions are as striking as that of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Beneath its vast rainforests and river systems lies an estimated $24 trillion untapped mineral wealth, making it one of the most resource-rich territories on Earth. The country holds the world’s largest reserves of cobalt, alongside significant deposits of copper, diamonds, gold, coltan, tin, and rare earth minerals essential to the modern digital economy.

Learn How to Leverage Your Story through our Story To Asset Framework.

Cobalt from Congo powers electric vehicles in Europe, smartphones in Asia, and defense systems in North America. Copper wires global cities. Gold underpins financial reserves. Coltan fuels the technology revolution.

And yet, despite this extraordinary abundance, more than half of Congolese citizens live in extreme poverty.

How does a nation so rich remain so poor?

This question has been asked for decades. The usual answers point to corruption, weak institutions, armed conflict, and governance failures. While these factors are undeniably real, they are not the origin of the problem.

They are symptoms of something deeper: a historical architecture of extraction designed in the 19th century and continuously modernized for the 21st. To understand Congo’s present, one must revisit its past.

The Birth of an Extraction State

In 1885, European powers gathered at the Berlin Conference to formalize territorial claims across Africa. The Congo Basin, larger than Western Europe was handed not to a European nation, but to a single man: King Leopold II.

Under the guise of humanitarianism and civilizing mission, Leopold established the Congo Free State as his private possession. From 1885 to 1908, the territory functioned less as a country and more as a corporate enterprise.

Rubber and ivory were extracted at scale, enforced through forced labor, mutilation, and systemic violence. Historians estimate that millions perished during this period.

The brutality of Leopold’s regime is well documented. Less examined, however, is the institutional template it created: a governance structure optimized not for citizen welfare, but for resource extraction.

That template contained several core principles:

- Centralized control of territory

- Alignment between missionary networks and administrative authority

- Suppression of local political structures

- Prioritization of export infrastructure over domestic development

When Belgium formally annexed Congo in 1908, the violence moderated, but the architecture remained intact. The colony was still managed primarily as a supplier of raw materials to European industry.

Independence in 1960 did not automatically dismantle that structure. It inherited it.

The Psychology of Control

Colonial systems rarely rely on force alone. They endure by shaping belief. Missionary education played a decisive role in this transformation. Schools introduced literacy, but often within a framework that emphasized obedience, hierarchy, and alignment with colonial authority.

Indigenous governance systems, spiritual traditions, and scientific knowledge were marginalized or dismissed.

See also The Life & Legacy Of Simon Kimbangu (Congolese Religious Leader) With Kiatezua Lubanzadio

The impact was not merely political, it was psychological.

As Nigerian author Chinua Achebe observed in his 1958 novel Things Fall Apart: “He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart.”

Achebe’s reflection captures a central dynamic of colonial intervention: fragmentation. When communal cohesion weakens, collective resistance becomes difficult. When people begin to doubt their own historical continuity, they become more susceptible to external definitions of legitimacy and progress.

Education systems across much of colonial Africa prioritized memorization over critical inquiry. European exploration narratives replaced indigenous geographic knowledge. Economic instruction centered on integration into global trade rather than domestic industrialization.

The result was subtle but powerful: a population trained to participate in a global system without controlling it.

From Colonialism to Globalization

The end of formal colonial rule did not end resource extraction. It restructured it.

Today, multinational corporations operate mining concessions across Congo. Cobalt from Katanga feeds battery production chains. Gold moves through international commodity markets. Timber and coltan travel complex trade routes that often obscure their origin.

Illicit financial flows compound the problem. Raw materials may be exported through intermediary countries, under-invoiced, or transferred through opaque shell companies. The cumulative effect is staggering: billions of dollars leave the country annually, capital that could otherwise fund infrastructure, healthcare, and education.

Meanwhile, development institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund provide loans and policy frameworks intended to stabilize economies and promote growth.

While many programs aim at reform and macroeconomic stability, critics argue that structural adjustment policies historically prioritized debt repayment and market liberalization over domestic industrial capacity.

The paradox persists: Congo exports raw materials at low margins and imports finished goods at high cost. Value addition occurs elsewhere.

In this context, a striking comment by former French president Jacques Chirac resonates: “Without Africa, France would be a Third World country.”

Whether rhetorical or candid, the statement underscores a structural reality: African resources have long underwritten European industrial and financial expansion.

The flow of wealth has largely been one-directional.

Conflict as an Economic Variable

Armed conflict in eastern Congo is often framed as ethnic rivalry or regional instability. While local dynamics are undeniably complex, mineral wealth is an undeniable factor. Armed groups have financed operations through control of mining zones. Cross-border smuggling networks operate in contested territories.

Instability depresses local bargaining power. It weakens regulatory enforcement. It obscures accountability. In such environments, extraction becomes cheaper and oversight thinner.

This does not absolve foreign actors of responsibility, but neither does it absolve domestic leadership.

Sustainable reform requires political will within Congo itself. Resource governance transparency, contract renegotiation, and institutional strengthening must originate domestically, even if supported internationally.

No external power can impose sovereignty.

The Internal Dimension

Blame directed outward can obscure internal accountability. Local political elites have, at times, negotiated contracts unfavorable to national interests. Corruption has diverted public funds. Governance failures have compounded external exploitation.

Yet internal weakness did not arise in a vacuum. Post-independence Congo endured Cold War interference, dictatorship under Mobutu Sese Seko, regional wars, and ongoing armed insurgencies.

Institutions were shaped under extraordinary pressure. Recognizing structural origins does not negate responsibility. It contextualizes it.

Congo’s path forward requires dual clarity:

- External systems have historically extracted value.

- Internal reform is indispensable for change.

Both truths coexist.

The Education Question

Perhaps the most enduring colonial inheritance is epistemological: how societies define knowledge.

Colonial education often trained intermediaries, administrators, clerks, and functionaries, to manage extraction systems.

You might also like Understanding What Is Behand The Conflict in Congo DRC, M23 and more – Tanignigui Siriki Soro

Post-independence states expanded access, but curricula frequently retained imported frameworks with limited adaptation to local economic realities.

Critical questions remain:

- How can education systems cultivate entrepreneurship in resource processing rather than solely in resource export?

- How can engineering and scientific training align with domestic industrialization?

- How can historical instruction restore continuity without romanticization?

The future of Congo depends as much on curriculum reform as on mining contracts. Nations that industrialized successfully did not merely export raw materials. They built processing capacity, protected infant industries, and invested heavily in human capital aligned with national development goals.

Congo’s demographic profile, young and rapidly growing, offers both risk and opportunity. If youth remain excluded from value creation, instability may persist. If mobilized toward innovation and industry, transformation is possible.

The Diaspora Factor

Congolese professionals abroad increasingly play a role in reshaping narratives and advocating transparency. Financial investigators, academics, technologists, and entrepreneurs are leveraging global networks to expose illicit trade routes and propose governance reforms.

Digital connectivity has reduced informational asymmetry. Civil society organizations track mineral certification. Journalists analyze supply chains. International consumers question sourcing ethics.

Pressure is mounting for greater transparency in battery production and electronics manufacturing. As the global transition to renewable energy accelerates, Congo’s strategic importance will only grow.

See also Renate From Brussels to Congo, The Blood Still Cries from the Soil: A journey In Search of the Truth

The key question is whether that importance will translate into equitable development—or intensified extraction.

Rethinking the Narrative

The prevailing global narrative often frames Congo as a “failed state” burdened by corruption and conflict. This framing obscures structural realities.

Congo is not poor because it lacks wealth. It is poor because the mechanisms governing that wealth have historically prioritized external beneficiaries and short-term gains over long-term domestic value creation.

Reframing the issue from moral deficiency to structural design changes the policy conversation.

It shifts focus toward:

- Transparent contract negotiations

- Regional stabilization initiatives

- Investment in local refining and processing

- Educational reform aligned with industrial strategy

- Strengthened anti-corruption institutions

Such reforms are complex. They require political courage, regional cooperation, and sustained civic engagement. But they are not impossible.

History shows that nations can redefine their trajectory when governance aligns with national interest.

Conclusion: Beyond the Paradox

The $24 trillion beneath Congolese soil represents more than mineral wealth. It symbolizes deferred potential.

For over a century, Congo’s economic structure has been oriented outward. Colonial administration established it. Post-colonial fragility entrenched it. Global markets modernized it.

Yet structures are not destiny.

As global supply chains reconfigure and African agency grows more assertive, an inflection point approaches. The same minerals that once fueled colonial exploitation now power renewable energy transition. Strategic leverage exists.

See also Peace Agreement Between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of Rwanda

The decisive factor will not be geology. It will be governance.

Congo’s future hinges on whether it can convert extraction into transformation, raw materials into industry, revenue into infrastructure, and demographic growth into productive capacity.

The paradox of extreme wealth and extreme poverty is neither natural nor inevitable. It is historical.

And what history constructed, determined leadership and informed citizens can reconstruct.

The question is no longer whether Congo is rich.

The question is who will shape the system that governs that richness in the decades to come.